Guitar players can pick the strings with their fingers, or they can strum them. It's rare for a guitar player to use only one of these techniques, and a masterful player like Mark Knopfler will seamlessly blend the two.

In marketing, there is a similar situation with direct response marketing and brand marketing. These are two marketing techniques that indie consultants blend.

Direct response marketing is the ideal marketing technique for bootstrapping; for helping a new specialized indie consultant build up the cashflow and momentum their new enterprise desperately needs.

Why this matters to you: The same usage of direct response marketing will make an established consultant look needy and untrustworthy. The difference, of course, is context. When the new consulting business has matured, we assume it possesses expertise that is valued and demanded in sufficient measure to support a more generous and less efficient form of marketing: brand marketing. If we see a supposedly established and successful consultant making heavyhanded use of direct response marketing techniques, we question whether they possess sufficiently valuable expertise.

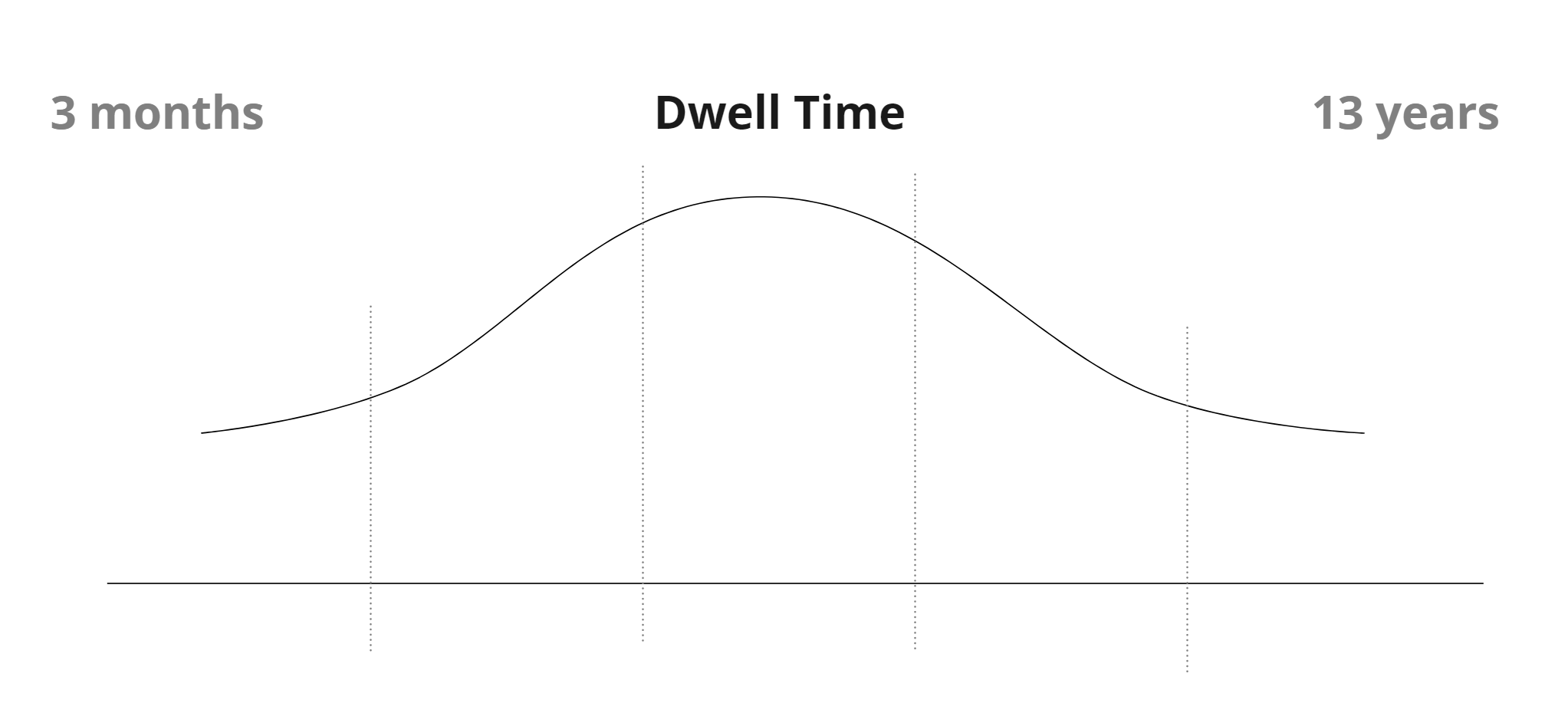

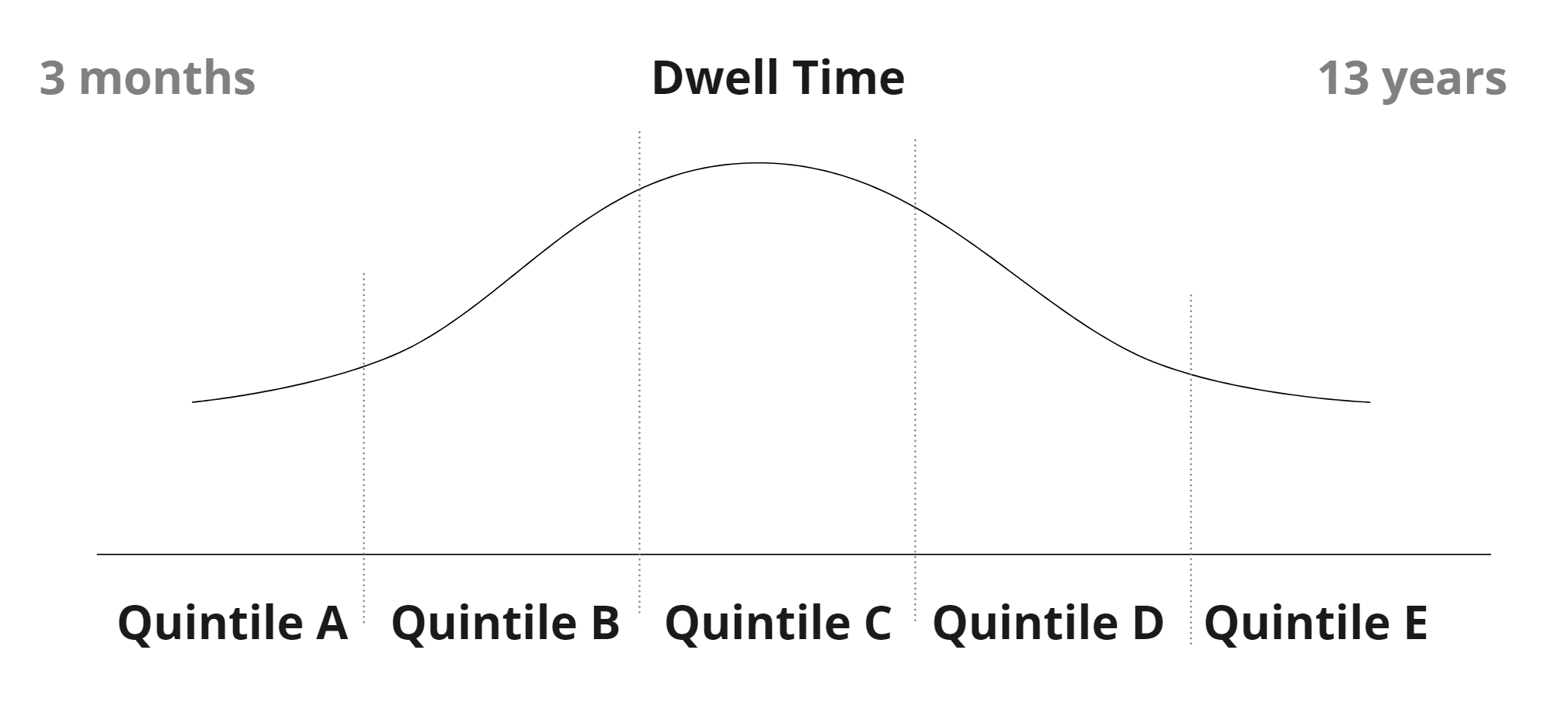

Let's imagine that a long-term study of companies that buy indie consulting services finds an average "dwell time" of 4 years between first becoming aware of an indie consultant and hiring that consultant. The distribution, however, is a pretty low, broad version of a normal distribution, and so there are lots of outlier situations: consultants getting hired after a 3 month dwell time, 13 year dwell time, etc.

(Diagram is to illustrate the idea, not convey scientific measurements. :) )

Let's further imagine that there's plenty of opportunity in this market, and so you can build a nice business serving any quintile of the market.

If you were just starting your indie consulting business and had limited runway, which kind of buyer would you want to attract?

You'd want buyers from quintile A, and you'd be smart to want those buyers. You would be giving up some things by focusing on those buyers, though. They might have unhelpful preconceptions about what they should budget for your services, for example. But, you would be getting something that is more important for your bootstrapper context: access to buyers who are ready to buy quickly.

If you were optimizing your marketing to speak to quintile A buyers, what would you do?

You would do what is known as direct response marketing.

Direct Response Marketing is a Form or a Button With a Funnel Behind It #

Direct response marketing has a sort of vocabulary that you'll easily recognize once you see it:

“To get the free bonus, send me your Amazon receipt showing that you’ve prepurchased 10 or more copies of my book.” (This is a call to action, or a CTA.)

“To receive this free email course, tell me what email address to send it to.” (This is a low-friction form used to collect signups or opt-ins.)

“To download this white paper, please tell us about your company demographics and needs.” (This is a gated content asset.)

“Buy this $7 e-book and learn how to increase your website's conversion rate.” (This is a low-priced product used to measure buying intent and collect contact information.)

“Attend this free webinar and learn how to price your services more profitably.” (This is an event used to collect contact information that will later be used to promote something.)

These are the vocabulary of direct response marketing. Direct response marketing may also make use of the following:

- Long form sales copy

- A sequence of emails that describes some pain or problem, spends time vivifying that pain/problem, and pitches a solution to that pain/problem (often part of what's called a digital marketing funnel)

- Money-back guarantees

- Testimonials

- Engineered pricing (a price schedule with three or more tiers designed to maximize volume, revenue, or profitability)

The genre of heavy metal music prepares you to hear distorted electric guitars, heavy drumming, and screamed vocals. There is a fun subgenre of novelty heavy metal music. In that subgenre, you have groups like Hayseed Dixie playing AC/DC songs on guitar, mandolin, banjo, and fiddle in bluegrass style. The difference is not the notes being played, it’s the entire tone of the resulting music.

Direct response marketing also has a certain tone to it:

- The goal of direct response marketing is to get a response from those we market to. This is the most fundamental, defining aspect of the genre. The “response” is not necessarily a sale. It might be some other kind of action: filling out a form, clicking a button, opening an email, attending an event, joining a waiting list, or the like. The larger goal of direct response marketing is to produce measurable results quickly, in weeks or months, rather than years.

- The ethos of direct response marketing is creating a personalized, one-to-one connection with prospects from the very first interaction.

- Direct response marketing will intentionally or accidentally collect data—the more individualized and complete the better—about prospects.

- Critically, direct response marketing is focused on problems.

- Direct response marketing often tries to manufacture or amplify urgency around the recipient taking some kind of action.

- A lot of direct response marketing focuses on the pain of the problem the marketer purports to solve. The pain of doing nothing. The pain of doing the wrong thing.

- Sometimes you’ll see direct response marketing make use of curiosity. The apotheosis of curiosity in direct response marketing is the clickbait headline. ("One Weird Trick…")

- Product or service benefits will often be stated in strong or exaggerated ways in direct response marketing.

The tools of direct response marketing are designed to yield an immediate sale or measure readiness to buy and then place those who are not ready to buy now in a different group to be "nurtured" or ignored. This makes direct response marketing the most efficient way to reach prospects who are ready to buy now or very soon (weeks or months).

Direct response marketing was pioneered in the days of direct physical mail. In that world, reducing the very real cost of the very physical mailing was a good way to increase profitability. This mindset of maximal efficiency has persisted even as the Internet has lowered the cost of digitally contacting a prospect to nearly zero (if it's a highly automated, near-spam style of outreach).

The high level characteristics of direct response marketing are:

- Measurable: We want to know who is responsive to a "buy now" sales message and who isn't so we can focus on the most responsive prospects.

- Personalized: We want to get the "right message" to the "right people" at the "right time" to maximize our ability to persuade them to buy.

- Efficient: Lower the cost of sale by having (relatively cheap) software and 1-time-cost copywriting replace human relationships and (relatively expensive) salespeople as much as possible

All of this is in service of one purpose: find buyers who are ready to buy now, or ones who will jump into a buying posture if a pain point is pressed hard enough. In other words: efficiently generate cash quickly.

In a bootstrapping context, this is the ideal approach.

As always, there are tradeoffs. Direct response marketing is not the ideal tool for developing future clients for an expertise-driven business. And the fact that it is so focused on efficiently generating cash quickly sends a subtle message that the business needs cash quickly, which causes many buyers to doubt that the business possesses self-evidently valuable expertise.

To overstate things a bit: you don't sell your stuff at a pawn shop if you can afford to wait for the best price. The very strongest usage of direct response marketing creates the ambiance of a pawn shop.

Brand Marketing is Something Non-Monetary to Buy Into #

The vocabulary and tools of brand marketing are recognizable, but less so than those of direct response marketing. The latter are often obviously pushing on a pain point or agitating for a sale, and it's easier to spot that kind of noisy stuff in action. Brand marketing, by contrast, is less visible because it's more like the water that fish live in.

If there's a non-monetary something to buy into beyond an immediate solution to an immediate problem — especially if this something is a philosophy, culture, or worldview — then we are looking at a brand as it exists within the indie consulting world.

If there's a "people like us" to join… if there's a "this is how we do things" to join up with… then it doesn't matter if the buying into is via giving the brand a bit of your limited mental bandwidth, saying to a colleague "hey, you might check this out", starting to adopt terminology, enlisting as an apostle, or actually buying the offerings; there is at least a nascent brand.

If some aspect of the something you could buy into immediately surfaces a name or a memory of a vivid experience involving a person, then we are talking about a personal brand. A personal brand is not being known, it is being known for something that we can buy into.

If you do some research into the question, "what is a brand", the consensus is this: it's the aggregate of how people feel about your business. I put it this way: it's the collective mental residue of the thousands of client, prospect, and market interactions you've had. This is all fine, but it doesn't help us know how to build an indie consultant brand. At best, this definition leaves us with the old adminition: "Just do good work and don't screw up your reputation."

How, again, are indie consultant brands built? By making intentional use of these inputs:

Gifts: Considered as a one-time thing, brand marketing is a gift with a logo on it. Considered as an ongoing process, brand marketing is the practice of regularly, intentionally giving your market gifts with your logo on it. The logo might be an actual logo, but it's more likely that thing your market buys into — a philosophy, culture, or point of view that is sufficiently distinctive so that it functions like a logo. The gift should be something that actually feels like a gift to the recipient, not cheap junk that's costless to you, and not something that would feel like a gift to you but not to your market. Gifts can be free, but things that are bought can also be gifts if they contain an amount of value that overwhelms the memory of the price. For example, a life-changing book lives on in memory as a gift even though it might have actually cost 10 or 20 bucks.

Impactful Experiences: The gifts might be tangible things, but they can also be intangible but impactful experiences. (My first wife was an alcoholic, so 12-step programs are both familiar and fascinating to me.) Alcoholics Anonymous is open to all, but attending a single meeting is remarkable because it gives you a visceral sense of what attending any of the other 115,326 meetings worldwide — attended or coordinated by more then 2 million people — would be like. You don't have to sample 30% of these meetings to understand what buying into AA would be like. That's a great example of how brands create impactful experiences.

Doing the work of becoming your market's water: NFL football swims around in a medium composed of Nike, Adidas, Under Armour and countless other brands. In the same way, anyone thinking about starting a small scrappy Internet-powered lifestyle business in 2010 swam around in the "water" of ideas that came from Tim Ferriss, Gary Vaynerchuk, Steve Blank, and a handful of others. If you bought "The 4-Hour Workweek" for $20 or whatever, you also had the option of buying in to the larger idea of "escaping the 9-5, living anywhere, and joining the new rich." It's easy to write the previous sentence with the same kind of smirk I get when I remember jamming out to Milli Vanilli in the '80's, but those ideas from Ferriss and Vaynerchuk did some people a lot of good. They were the gift of a new way of thinking and seeing things.

In other quarters of businesstown, the water we swim in is the ideas of the Business Model Canvas or the Wardley Map. Having observed Simon Wardley with great interest for some time now, I can tell you that he absolutely is on a mission to make his eponymously named approach to value chain mapping into a dominant part of the "water" that tech entrepreneurs swim in. He pursues this mission with an admirable combination of generosity and ferocity. His work offers people a method (the Wardley Mapping approach) and a larger set of ideas (Wardley's Doctrine Patterns) to buy into. Or not! That's a big part of brand marketing: the buy-in is totally voluntary.

"Business" or "startups" or "entrepreneurship" are massive ownerless open systems, so no one person will contribute all the "water" that members of these systems swim around in, but a brand can certainly have outsized influence. Here's how they build that influence.

1: Reach or impact at the expense of personalization or focus: Brand marketing often trades away personalization or focus to obtain more reach or impact. Standing on this stage at a O'Reilly event deprives Simon Wardley of an ability to individually personalize his message. The audience contains whoever attended, and the YouTube recording of the talk reaches whoever searches for it or gets it recommended via the YT algorithm or a writer like me. Simon has traded away the kind of micro-targeting capabilities that demographic or search ads would offer, for example. I would argue that, given his purpose, he's made the right trade and has indeed obtained the reach and impact that support his mission.

2: Use institutions and broadcast platforms: Because brand marketing is willing to trade away personalization in exchange for reach, those building a brand will sometimes informally partner with institutions that can help them reach their market. Institutions, in our usage here, are organizations within a market that are sufficiently important and ossified. Within the indie bootstrapped SaaS world, a conference called Microconf.com is an example of an institution. Dreamforce and re:Invent are similar institutions in different worlds.

A podcast or a website RSS feed is an example of a broadcast platform. You have no control over and extremely minimal knowledge about who listens or reads what's being said on that broadcast platform. You need to compensate for that lack of control somehow. You do that through relevance and offering something for people to buy into, and you do those things by focusing on presence.

3: Presence: This is shorthand for being present with your market. I observe direct response marketers who are present with their market at exactly one point ever: while they are executing a product launch. I'm as introverted as a human can get and even I'm offended by this behavior because it's so patently transactional. I'm not saying we should all imitate Mother Teresa, and I'm not advocating the kind of boundaryless availability that would undermine your status as an expert, but if you want to lead, inspire, or change your market, you will have to be present with them.

The Internet has given us a magnificent variety of ways to be present with a market, and these digital, remote, asynchronous methods of presence supplement the more expensive and — for many of us — emotionally taxing in-person forms of event attendance.

Despite these advances, presence always involves at least the emotional labor of curiosity, thoughtfulness, and caring about the wellbeing of your market. The payoff for this investment is insight into your market, and that insight combined with a willingness to lead can translate to revenue that is commensurate with your broad impact on the market.

4: Implicit CTAs or soft CTAs: Brand marketing will often make use of implicit or very "soft" calls to action (CTAs). This is consistent with the larger idea of building a "volunteer army" of those who have bought into something beyond a solution to an immediate problem.

Brand Marketing Genre Expectations #

As with direct response marketing, brand marketing has a certain tone to it.

- Bearing in mind that we're unapologetically in a profit-seeking context, not a Mother Teresa context: brand marketing is driven by a purposeful generosity — using gifts to push towards a specific goal, not a Boy Scout-style "have you done your good deed for the day?" reactive generosity. I'm thinking of Small Batch Standard (SBS), who are consulting CPAs focused on the craft brewing industry. When COVID began stress-testing their market, they released a piece of IP. The conscious and unconscious thinking of direct response marketing would have used this piece of IP to find and motivate Quintile A buyers. Instead, SBS published it as a totally free gift (with a logo on it). Their purposeful generosity was aligned with the long-term health of their industry which is aligned with SBS's long-term health. SBS didn't sell this IP at a pawnshop; they turned it into a purposefully generous gift with a logo on it.

- Brand marketing tends to be connected to the market's culture in a way that direct response marketing often is not. Copywriter Gary Bencivenga once said "problems are markets". In those 3 words he crystalized the direct response marketer's focus on problems rather than the culture and health of the group of people who form a market and the larger march of progress that solving those problems should be a part of. I think of Blair Enns, whose empathy for the pain that the cultural normalcy of free pitching causes creative professionals led him to create a training business that provides a path out of this pain and into a world where you can win without pitching. The brand marketer's care for the culture and people in a market expresses itself through their usage of presence and partnership with the market's institutions.

- Brand marketing tends to focus on fulfilling an aspiration rather than on removing pain. If the brand has a point of view, that POV is broader or more expansive than any one problem. Imagine that the brand is a colosseum. We can enter the colosseum through any number of doors or gates, but once we're inside, there is one show happening. Inside the "brand colosseum" is the non-monetary thing — the method, philosophy, culture, or worldview — that the brand was inviting us to buy into. In some cases, the brand creates culture by building connection between those who interact with the brand by admiring it, talking about it, sharing it, advocating for it, using it, buying it, etc. I think of my friend David C. Baker's powerful personal brand (again, not being known but being known for something you can buy into) as a colosseum where through the multiple gates of his books, seminars, and consulting, people who don't know each other buy into the culture of doing good work but making great decisions that ties all his offerings together. When you think of problems as markets, any sufficiently juicy problem becomes a potential direction for your business. When you instead model your business as a colosseum, then the gates all need to lead to the same place. For many indie consultants, the center of their "brand colosseum" is an aspiration they invite you to buy into.

- The final aspect of the tone of brand marketing: the relevant time horizon is years or decades, not weeks or months. This opens up the possibility of developing customers in Quintiles B - E rather than regarding them as a form of waste or inefficiency. Chris Do of https://thefutur.com leads with this mission statement: "Teach one billion people how to make a living, doing what they love." This doesn't — can't possibly! — compute for the direct response marketer. There will probably never be 1 billion prospects in Quintile A of any market at any time between now and the heat death of the sun. But the brand marketer can consider the possibility of offering 1 billion people something to buy into over the next 20, 40, or more years. And maybe they're audacious enough to actually believe they can.

How do you build a brand? Give the market something to buy into beyond your ability to solve some immediate problem for them. That raises the next question: why would the market buy into something beyond an immediate solution to their problem. More generally: why do we humans do anything beyond solving problem X and then getting back onto the sofa and into our Netflix account ASAP? Why do we aspire to anything beyond corrections that maintain the status quo?

I don't have a great answer for this other than: some people just want more out of life than Netflix and chill, and some will look to brands — perhaps your indie consulting brand — to supply them with this purpose or a plan for getting something more out of life.

It's a really good question that I don't mean to dismiss, but I'm being honest when I say I don't really know why. I do know, however, that a metric ton of energy, time, and money is spent along these aspirational/improvement lines, and so I don't doubt that if you give your market something — some aspirational purpose — to buy into beyond your ability to solve some immediate problem for them, plenty will buy in, and their buy-in will be proportional to your generosity, presence, and vision.

The Direct Response Trust Ceiling #

I don't want to overcook this point because, look, at the end of the day, a lot of things can work, and a lot of so-called rules have bedeviling, idiosyncratic exceptions. But I do want to make clear that at some point, if you are using direct response marketing during your business bootstrapping phase, you will need to move away from pure direct response and towards a blend of direct response and brand marketing. It's a variation of the old truism: what got you here won't get you where you're going (if where you're going is cultivating rare, self-evidently valuable expertise).

I think the reason you must make this transition comes down to neediness. Direct response marketing makes you look needy, and we humans have a finely tuned nose for neediness.

Your Quintile B - E Prospect: "Why did you write 5,000 words of pushy copy to sell me this book?"

What they imagine you saying if you had been given truth serum: "I have a lot of persuasion ground to cover to convince you it's worth $49."

Prospect: "Why did you send me 5 emails on closing day of this launch?"

Truth serum-dosed you: "I need to eek out a slightly higher conversion rate because that's how I measure the effectiveness of my marketing."

Prospect: "Why do you have 20 testimonials on this page?"

Truth serum-dosed you: "Because I need to overcome objections through HTTP rather than through a conversation."

Prospect: "Well why do you do all that stuff?"

Truth serum-dosed you: "Because I can't afford to sell my services the way a normal expert does. I need the efficiency of direct response marketing."

It's not that your buyers are evaluating your marketing as an expert in marketing. But they are sizing you up as an expert compared to other experts they've seen, heard about, and experienced, and the problem that direct response marketing creates is that those other experts don't have to do it. Their expertise is self-evidently valuable. If they practice a licensed profession, they often plug into a system that gives them opportunity without them having to hustle for it.

If you act like your expertise is not self-evidently valuable, then you create a problem with more sophisticated or less desperate buyers. An overly-strong usage of direct response marketing sends the signal that you need the efficiency of this style of marketing, ad this sends the signal that your expertise is not sufficiently valuable or in-demand.

Transitioning From DR to Blended DR /Brand Marketing #

One read on the last 2,792 words would be to think that I'm trashing direct response marketing through the lens of how superior brand marketing is. That's not what I'm trying to do, but I could understand that read on things. I do have an agenda here, after all, so let me be clear about that. :)

I do believe that more indie consultants should aspire to practice brand marketing because more of y'all being able to do it would mean that more of y'all are able to do it, which means more of y'all have powerful, sustainable businesses, and that's the fundamental reality I'd like to see more of.

There is, to be honest, a small measure of woo-woo New Age thinking at play here too. If I can persuade more of you to intend to be able to do brand marketing, then more of you will focus on the health and wellbeing of both your business and your entire market — not just a limited focus on serving Quintile A buyers — and some of you will succeed at this difficult long game and then I will have gently tilted the playing field in a direction that supports my desire for a better world mwoohahahah!

The reality is that even the most generous, successful indie consultant will blend brand and direct response marketing.

I recommend an experiential case study: join the audience of any person I've named in this article and see what you see. Do you see lots of forms/buttons with funnels behind them? Do you see colosseums with gates leading to some non-monetary something that you are invited to buy into? Or do you see a blend of both, where the forms, buttons, and funnels are the gates to the colosseum where you find that book A or course B or service C all connect you to the same brand culture?

Jonathan Stark is another good experiential case study I recommend to you. Join his email list and you'll see a brand colosseum in action. There are direct response-style offers. These are the gates to the center of his brand colosseum where lies the invitation to buy into this aspiration: completely transcend hourly billing. There are other subtly varied ways to blend brand and direct response marketing to construct your brand colosseum, but nothing beats seeing someone actually do it, and Jonathan along with other folks named earlier in this article are doing it. (Except for Gary Bencivenga. He's probably a great dude, but I bet when he dies he stretches the truth about his birth date by 10 years and has a direct response-style long-form sales letter engraved on his tombstone selling you a life-extending pill that his estate collects affiliate fees on.)

How to Build Your Brand Colosseum #

Some marketing is ephemeral, and some is not. Your investment in direct response marketing will leave you with a "residue" of various direct response marketing assets (landing pages, sales pages, etc.) and the intertia of doing things a certain way.

As you shift to a blended direct response/brand marketing approach, that residue and inertia doesn't just go away. You'll have cleanup to do.

The cleanup might involve removing a tone of pressure or hype and replacing it with a more factual, objective tone. "Seven reasons why brain surgery will change your life for the better, overnight!" gets replaced with "What you need to know to make an informed, low-risk decision about brain surgery".

You might drop engineered pricing, or add integrity that was missing when you first started using engineered pricing. An example is my first book, The Positioning Manual for Technical Firms. I wasn't dishonest with my usage of engineered pricing for that book, and without it 2,154 sales would not have generated $100k-plus in direct revenue that was sorely needed during the bootstrapping phase of my business, but the $49/$99/$350 price points weren't always a good representation of the value of those 3 packages, especially the middle tier package.

What's as important as the cleanup: figuring out and building out the inside of your brand colosseum. Brand marketing is a gift with a logo on it, and it's also offering your audience a non-monetary something to buy into. What is that something?

It's often not easy to figure out, nor is it obvious. I ask those who join my email list to tell me about their vision for impact. 53% choose not to answer that question at all, and many of those who do answer it describe something that is a nice benefit or the outcome of a project (one recent example: "I will help my clients streamline and automate processes from weeks to hours.") but is not something that anyone could buy into beyond the scope of a single project or initiative.

When someone articulates a worthwhile center for their brand colosseum, you feel it. The role of squishy emotions are what makes this stuff so hard to turn into a simple implementation recipe.

Off the top of my head, here are some visions for impact that meet this bar:

- DevOps is really about improving communication within the organization.

- It's past time for embedded software developers to embrace modern software development practices.

- Hourly billing is nuts. It causes both you and your clients unnecessary pain and conflict. You can transcend hourly billing.

- Management consultants are wasting your time and money and are actively harming your organization. You can instead learn a simple value chain mapping technique that improves alignment within the organization and helps your org compete more effectively in the market.

- Your website content can be as clear and impactful as a great book, but with far more reach.

- Learning how to make better business decisions is what will evolve your business into something you can sell or retire on.

I could go on, but you get the picture. At the center of your brand colosseum is something that people can buy into. Something they can join or feel a part of. Something that's better if they're not the only one doing it or believing it.

Repeating the illustration from above:

The effective blend of brand and direct response marketing comes from effective alignment between the entrances to the colosseum and the non-monetary something that's within the colosseum. Those entrances are where the direct response marketing shows up most prominently.

Maybe one of the entrances is a very problem/pain-focused book, course, or workshop. The web page that describes this product looks like a sales page that describes the pain, describes the dream of transcending this pain, describes how the product will fix the pain, and provides social proof that the fix is effective. Maybe there's an email course designed to speak to Quintile A or B prospects who need a bit more risk-reduction before they buy. Maybe there's a paid ad campaign that uses data and personalization to reach those who might be suffering this pain.

The book or course delivers the promised solution, and it also provides an introduction to a non-monetary something that folks can buy into. The course content is a fractal of the philosophy, POV, ideal, identity, culture, shared aspiration, or distinctive approach that lies at the center of the brand colosseum.

If you can build out this something that lies at the center of your brand colosseum, then you have an incredibly valuable asset. You have a third thing that you can talk about. You already had the first two: 1) yourself, and 2) your ability to solve a problem or create an outcome. Those 2 are enough to build a great indie consulting career on, but this third thing is incredibly powerful: 3) something bigger than yourself that you can invite people to buy into.

If you're seeking broader impact, this third thing can get you on bigger stages.

If you're seeking deeper impact, this third thing can recruit a volunteer army rather than conscripts.

If you're seeking more revenue, this third thing can attract bigger audiences.

If you want to connect with people beyond Quintile A, this third thing gives them something to think about or be challenged by — something that brings them back to you when they are ready to buy.

If you're trying to transform an industry, this third thing means you don't have to do all the work yourself.

All of this is why, as your indie consulting business matures beyond the bootstrapping phase, you should strive to move beyond pure direct response marketing to a blend of brand and direct response marketing.

All of this is why you should build a brand colosseum.