I might be a bit obsessive about defining things, but hopefully that obsession is mostly applied to things that are under-defined, actually important, and can benefit from a bit of defining. The notion of "point of view" fits into this category.

Lots of consulting advice-givers who I respect gesture at the importance of point of view. They say:

- You should have a point of view.

- You should have a contrarian or polarizing point of view.

- You should have a strong point of view, one that might challenge your clients' beliefs or assumptions.

But what is this point of view thing? I've been working for literally years to answer that question in a useful way. Quite frankly, this article will probably be more of a write-to-disk-checkpoint for that process than an unveiling of a conclusive endpoint, but I think it will be useful and thought-provoking for you nevertheless. Here goes.

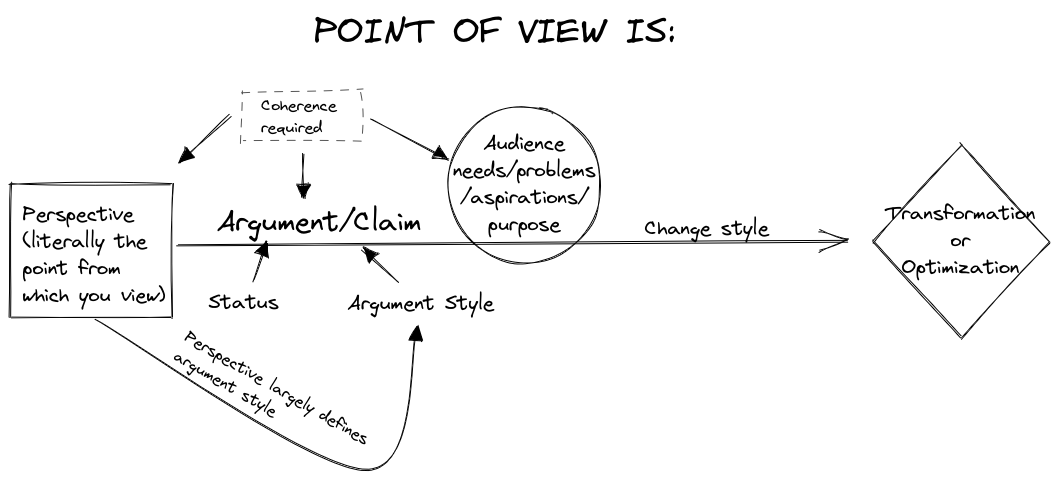

A point of view is an argument (a claim of truth, supported by evidence) made in service of your audience's best interest, made from your clear and relevant perspective.

The Functions Of A Point Of View #

A point of view actually does stuff in the world and within your relationship with prospects and clients. A POV is an active force in 4 ways.

1) Differentiation: Because few of your direct competitors care to challenge how their clients do things, a point of view that argues for change is almost always de-facto differentiating. To say "y'all should be doing things differently and I can prove it" rather than "let me help implement your agenda item X to your specs with quality and speed" sets you apart. This differentiation can create distinctiveness and enhance mental availability, such that you are more referable and more memorable to prospects who don't need your services now but eventually will. POV can also be a differentiator of last resort between consultants with roughly comparable expertise, or expertise that a prospect is not sophisticated enough to evaluate properly.

2) Service: A good point of view serves the health or progress of your market or audience. That service could be in the style of an intervention with a drug addict, helping a beloved choose a flattering outfit for an important event, or advising a child on a practical money-making college major against their strong preference for art history. In other words, it's not the frictionless service of a good waiter at a restaurant and it might involve provocation or well-meaning conflict. In the case of thought leadership, it involves a protracted campaign of arguing for change. But at the end of the day, you rest easy knowing that your point of view, and any conflict it engenders, honestly seeks the wellbeing of your market.

3) Screening: Because your point of view will contain an argument or claim that reasonable people could disagree with, your POV will serve a client screening function. Sure, across enough client engagements, you'll eventually get hired by a client who says something like "I completely disagree with your approach but I hired you anyway because...". In the main though, you'll get hired by clients who are psyched about how your POV agrees with theirs, or who hear you saying something they feel but couldn't quite articulate until they heard you express it through your POV. And critically, you'll get not hired by pain in the ass clients who would resist your approach or ignore your advice.

4) Positioning: A POV positions you as a consultant rather than an order-taker. Order-takers are careful to emphasize their flexibility and eagerness to serve, with few boundaries beyond being able to bill hourly for that flexibility so the client bears the cost of any inconvenience. While a consultant who seeks 100% client satisfaction may exhibit significant flexibility ("sure, we can use your project management system; no, I don't care what video call software we use -- what are you comfortable with?"), an inner hardass will emerge when a client asks for flexibility around something your expertise knows is non-negotiable. Clients will have gotten a preview of these non-negotiables because they are often the content -- the primary argument -- of your point(s) of view, and you have surfaced those during early sales conversations. Thoughtful, expertise-based non-negotiables in service of client wellbeing differentiate consultants from order-takers.

The Components Of A Point Of View #

There are several moving parts that constitute a point of view. Most good points of view emerge organically from your desire to serve your market with repeatable, scalable expertise rather than improvising one client solution at a time, so as I walk you through the components of a point of view, don't get pulled into reductionist thinking about how you could engineer or construct a point of view from a box of components. Rather, think of me as a parent who is telling you, the pre-teen, what is about to happen to your body in puberty. Or don't, if that weirds you out. :) But it's the same intent: you probably don't understand how a point of view really works and even though you probably don't need to understand exactly how it works, it'll help to be roughly familiar with the underlying system's function.

The Central Elements #

There are 3 central elements to a point of view.

1) Argument/Claim: The most central element of a POV is its argument or claim. In POV land, arguments and claims center on one or more of the following:

- This is true, or is an under-appreciated truth that would help if properly appreciated

- This is how we/you should do X

There are plenty of subtle variations on the above. For example, "How we should do X" could be "Why Y is holding us back and why X is what we should do about it", or any number of other variations. The power of a POV is not its precise grammatical structure but the fact that it bothers to make a claim or argument in service of the market's improvement. If the argument or claim is already accepted by the market, then congratulations, you have a boring, likely-impotent POV! ;-) Most claims or arguments will be contra the status quo and pro the future benefit or wellbeing of your market, and this tension with the status quo is really the source of the POV's ability to attract interest, buy-in, and action.

2) Relevance: A good point of view is relevant to the market or audience's needs, problem(s), aspiration(s), or purpose. My point of view on infrastructure in rural America is probably not relevant to your concerns with indie consulting, and that's fine! I'd be foolish to wish otherwise. As in the diagram above, a good point of view's argument intersects with its audience's concerns.

3) Outcome: A good point of view pushes things towards a desirable outcome. That outcome generally fits under the umbrella of improved wellbeing for your market/audience, but you should be able to more specifically describe the probable outcomes of accepting any given POV.

Jonathan Stark has a wonderfully relevant POV, the headline version of which might go like this: hourly billing is nuts. It's crazy, and it's a cancer on the professional services. On the list of probable outcomes for those that buy into and implement this POV is higher revenue or profitability, and higher satisfaction with their self-employment. Certainly if enough people embrace Jonathan's POV, someone will have a better sex life too and attribute it back to the POV. I'll have to check with Jonathan before I die on this hill, but I think "better sex life" is not a probable outcome of Jonathan's POV. The actual list of probable outcomes is lengthy and compelling enough to not suffer from the absence of "better sex life".

A POV does not need to lead to a completely revolutionary or transformational outcome, either. It's fine for your POV(s) to argue for something that is incremental optimization rather than rapid transformation, revolution, or reinvention. If you look with "POV envy" at a somewhat more transformationally-focused POV like Jonathan's, remember all the risk-averse businesses out there that will feel safer with your advocacy for lower-risk incremental optimization and smile when you think about getting paid to help them stay within their preferred risk budget. The world needs a range of consultants using a diversity of styles.

The Contextual Elements #

There are 4 contextual elements to a point of view. Because a POV emerges from a human being who cares about a market they have specialized in serving, the POV will be shot through with unique human-fingerprint-like stylistic qualities. In fact, if Jonathan Stark and I both cared passionately about the same audience and the same specific outcome, we would each have distinctively unique points of view by which we argue for that outcome because we are substantially different people (though both with great hair, I am told). This difference in POV would be a product of a difference in context. Those 4 contextual factors:

1) Perspective: You stand somewhere in life; you can't help but do so. Your location partially defines what you see. A person for whom winning at standardized testing has always been easy sees annoying but trivial little games standing between themselves and the opportunities that are gated by that testing. A person who struggles with standardized tests sees heavily guarded doors in front of those same opportunities. Same thing, different perspective.

An outsider to an industry might see opportunities to do things better if only X, an insider will remember the times variations of X have been tried before and failed and see 10 reasons not to try X. A scientist sees a need to evaluate support for a new initiative with a quantitative survey, a visionary sees a need to rally the troops with an inspiring afternoon workshop.

A point of view is called that rather than "an opinion" because the point from which you view (see) things is such an important determinant of what you see and how you argue for change. Becoming aware of the contextual factor of perspective invites you to explore some important questions:

- Do those who you hope to influence with your POV share a similar perspective with you?

- Whether they do or not, how might the overlap (or lack thereof) in your perspectives be a source of power?

- Is there something you have been taking for granted in your perspective that could be a source of power? Are you adept with the data your audience hungers for more of? Have you accrued experience that could inspire or soothe your audience?

Never worry that there's anything wrong or inadequate about your perspective. Always look for the ways it grants your POV power -- they are there waiting for you to discover and leverage them.

2) Argument Style: In your POV you are making and supporting an argument or a claim. As you do so, your style -- the way you phrase things, the examples you use, the expectations you have of your audience -- will land somewhere on a spectrum running from forceful and disruptive to gentle and nurturing. This style is not wired into you through your DNA and so can be modulated if you want. This again invites exploring a question: what argument style would best serve your efforts to serve your audience's best interest?

3) Status: Your status as perceived by those you seek to serve is partially a product of how you present yourself and partially a product of your unalterable personal history and perspective. An ex-big 4 consultant will have a pedigree that they can accentuate or minimize when interacting with their audience. An industry outsider has a lack of pedigree that they can also accentuate or minimize. Combined with intentional framing (ex: "I don't have a background in X, but that also means I'm not steeped in the bad habits of X."), both can be powerful. Don't get too in your head about it, but do explore the question: how might you use your status with your audience to best serve their best interest?

4) Change Style: Finally, in working with clients to help them make things better, you'll have a natural change style -- a natural way of helping them approach uncertainty, the status quo bias, risk, discomfort, institutional inertia, communication friction, and so forth. Like your argument style, this is learned, not hardwired (though many of us have un-helpful hardwiring we need to override with better learned behaviors). The most effective consultants have usually invested heavily in developing a change style that contributes to their effectiveness. But we all have our limits. Know thyself in this area, and consider to what extent there is coherence among what you are arguing for, your argument style, your change style, and your audience's needs.

All together, the 3 central factors of your POV (argument, relevance, and outcome) and the 4 contextual factors (perspective, argument style, status, and change style) combine to create a human-fingerprint level of uniqueness to any given POV. My goal in explaining the components of a POV is not for you to get in your head about optimizing each element in some way. Rather, I hope this merely leads to a deeper level of self-awareness that you use to find leverage to more effectively create the change you want in your market.

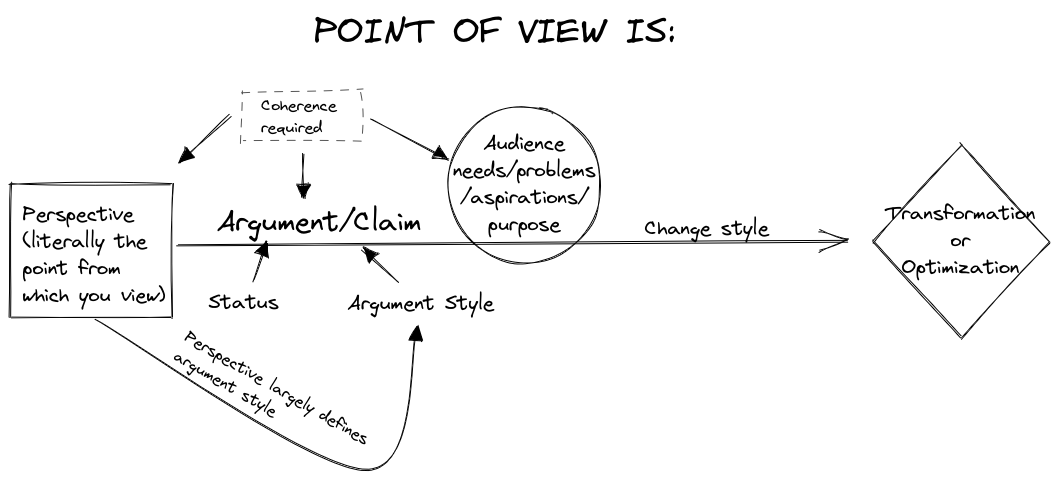

(Same diagram as before, just repeated here for convenience and emphasis now that I've explained every component of the diagram.)

(Same diagram as before, just repeated here for convenience and emphasis now that I've explained every component of the diagram.)

Developing Your Point Of View #

Points of view emerge from a living relationship between you, your concern for your market, and your market. Can they instead be engineered? Manufactured?

Not that you or I have any experience in songwriting, but I think it's a bit like songwriting. You can nurture points of view (and songs) into being. You can create the pre-conditions that make it more likely for a point of view to emerge. You can take a mess of opinions and sift through for good "POV material". You can polish a raw POV into something more impactful and effective.

But I do not think you can engineer or manufacture a POV from nothing. That begs the question: what is the something you must have to nurture a POV?

You have to care about your market's improvement. There is a much stronger causal relationship between genuine care for your market's wellbeing and impactful points of view than there is between expertise and POV, and between fame and POV.

In other words, a good POV is a second-order effect of caring about your market's wellbeing. As you've seen if you've read this far, there's quite a lot to say about POV itself, but there's nothing more to say about what births a good POV than this: you simply have to care enough to stick your neck out with a thoughtful perspective on what would make things better for those you seek to serve.

(This is part 1 of a 2-part article. Part 2 is here.)