This question came from a new email list member: "I don’t have a lot of client work under my belt. How can I convince my target clients to hire me when I have no relevant case studies to point to (yet)?"

There are alternate approaches that reliably reduce or eliminate the need for case studies. I'll describe them here, and as I do, you'll think, "Wow, these require more effort than case studies." That's correct, and this highlights the under-noticed way that a quest for efficiency drives so many of our assumptions about what we might call "good marketing".

Efficiency is great in many contexts, but I am against an unquestioned pursuit of efficiency because this often takes us undesirable places and gets us there gradually and then all at once, before we can notice, stop, and reverse course.

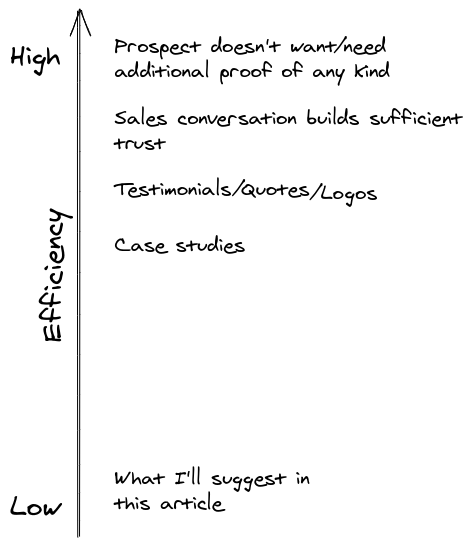

Case studies don't convince anyone to do anything (the internal storytelling we do with ourselves is what does the self-convincing), but they can at least lower the perceived risk of working with a consultant and at most earn some trust. Additionally, they're a pretty efficient way to accomplish this. If we ranked various ways of lowering perceived risk or earning some trust, we'd get something like this:

Referrals can cause a prospect to not need or want any additional proof of your competence. And there are trust-related edge cases: maybe the prospect just likes you, is "feeling lucky", thinks the project isn't that important, or is tired of interviewing candidates and just hires you, etc. And certainly an hour or three of sales conversation can get some folks trusting you enough to move forward in the process without them having seen any case studies. These more efficient trust-builders do happen from time to time, but we can't count on them, so they're not an answer to the "no relevant case studies" question.

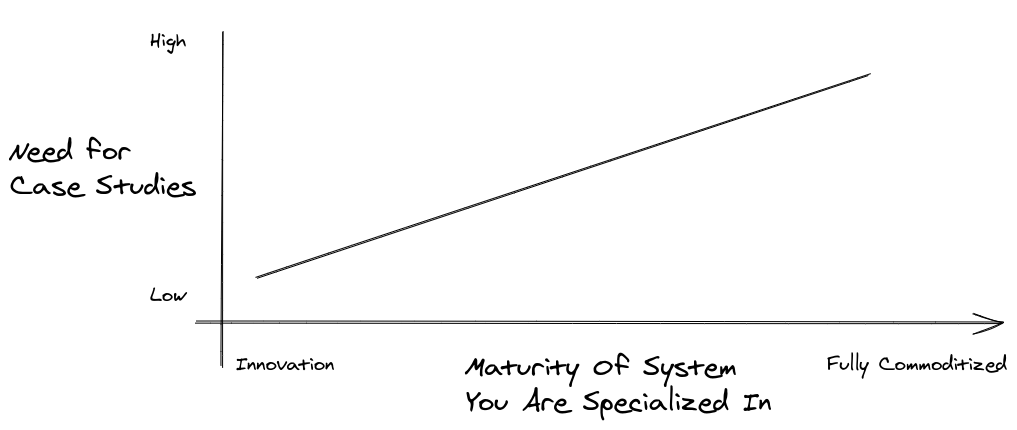

These "no case study required" situations are more likely to happen when the system is closer to the innovative end of this spectrum.

The final note before I get to the how-to part: We owe our clients a solution that tries to fit their risk profile. The reason it's even possible to do what our questioner is asking is that some clients can manage more uncertainty about whether we'll do what's promised and more potential for harm if we don't. This range of client risk tolerance creates room for us to level up in significant ways and enter new domains of expertise through the "side door".

In other words, what's "responsible" and "professional" is defined by our clients and their risk profile, not some across-the-board standard for every indie consultant. This is the beauty and (sometimes) terror of practicing an unlicensed profession -- we can often will our way into new opportunities and new levels of expertise.

This, to be clear, is enabled by the constant exogenous change the Buddhists are speaking of when they say the only constant is change. The tide of constant change will, often enough, bring together two ships: a risk-tolerant client and a risk-tolerant consultant. The tide of change looks like this: platforms rise; academics crystallize and simplify ideas and market them to the best-paying audience around (businesses) and then those ideas become TED talks and trends; platforms fade into irrelevance; government policy and spending shapes industries; innovations break through into mass adoption, etc, etc. The result of these tides and this meeting of two ships is, often enough, a client who gets an outstanding level of help initiating or responding to change and a consultant leaping into a new level of expertise, authority, and a more profitable service delivery model.

Go Deeper:

How To Bypass Needing Case Studies #

You bypass needing case studies by creating one or more of these alternate content assets instead:

- An astonishingly vivid general-purpose problem diagnosis.

- A meaningful improvement on the usual hand-wavey description of process.

- A short book on the topic.

There are a few other helpful approaches I'll lightly touch on towards the end of this article, but the 3 content assets above are things you can do without any actual client work under your belt. Because you, dear questioner, are new at your area of focus, creating these content assets will probably feel quite risky to you. You might hear yourself saying, "What if I'm giving bad advice in these content assets?" As my friend Brad Farris wisely advises, keep your mental focus on your desire to serve and help your clients improve their condition. This is the best antidote to impostor syndrome.

1: Diagnose The Problem Astonishingly Well #

Think about these two hypotheticals:

Specifically, would those two scenarios share any common outputs? I claim that they would share this output in common: in both scenarios you'd gain the ability to deliver a clear, insightful, empathetic, vivid diagnosis of the problem. Scenario A would supply you with far more nuanced, contextually-grounded insight into what makes for a good solution, but Scenario B, with 2% of the effort of Scenario A, would deliver a functionally equivalent ability to vividly describe the problem. That's leverage, baby!

It's surprising, but your clear, insightful, empathetic, vivid description of a problem leads many people to assume that you can help solve that problem. The two don't necessarily go hand in hand. It's not so hard to diagnose what's created a warming climate on planet Earth; solving that problem is another thing entirely!

Even though problem diagnosis skill and problem solution skill are not correlated, delivering a vivid, accurate-feeling diagnosis often leads the problem sufferer to assume that you also can deliver a remedy. As part of this assuming, they'll often advance you bit of unearned trust to suggest or implement a solution to their problem, or they'll be willing to "trust the process" while you implement your solution.

This actually isn't a terrible heuristic. Someone who has studied the problem enough to deliver a vivid, detailed diagnostic probably does have some reasonable ideas about the solution, and if the solution space is not commoditized -- meaning the solutions are not obvious standardized ones -- then this heuristic is likely to filter for people who have ideas worth considering about the problem and solution.

How do you, dear questioner, get to where you can diagnose the problem astonishingly well? You talk to people who have the problem, listen closely, ask them lots of probing followup questions, and look for patterns in what you hear. Every aspect of this approach has both primary and secondary benefits:

- Talk to people who have the problem:

- Primary benefit: learning about the problem.

- Secondary benefit: learning how to find people who have this problem, which you'll need to do more as you ramp up marketing.

- Listen closely:

- Primary benefit: learning about the problem.

- Secondary benefit: learning how to listen without rushing to prescribe a remedy, which will make you a better salesperson and consultant.

- Look for patterns:

- Primary benefit: learning about the problem.

- Secondary benefit: moving from delivering 1-off solutions to delivering repeatable solutions, which increases profitability.

The secondary meta-benefit of this approach is that you start to inhabit the layer above individual clients, which means you start thinking about problems and opportunities that effect segments, groups, and ultimately an entire industry. This is the domain of experts and thought leaders, and they relate to their clients from this perspective of seeing and thinking about the whole industry.

2: Far Exceed The Normal Process Bullshit #

The way many firms talk about their process is problematic. Understanding this problem -- and using a discussion of your process as a way to bypass needing case studies -- starts with knowing this:

- If the solution space is closer to commoditized (standardized, modularized), then having a robust, repeatable process is table stakes. Your process will be very similar to what others in your space use.

- If the solution space is un-commoditized (novel, emergent, chaotic), then you need a more flexible process, which might be robust and repeatable but it will be unique to your firm -- it won't be industry standard.

If prospects sometimes or often issue RFPs for the work you do, then your space is very likely closer to the commoditized end of the maturity spectrum. Even if you never respond to those RFPs, if the problem is an RFP-able problem, then the solution is somewhat or very commoditized (again: standardized, modularized).

It's disappointingly common for firms that are actually in a commoditized solution space to talk about their process as if it's a process for an un-commoditized space. Clients are flattered to think their problems are soooooo unique and special. Firms flatter themselves when they artificially inflate the level of creativity necessary to create stuff that's merely functional and distinctive but not actually innovative.

A certain amount of this self-flattery is productive because it creates a context where a calcified client can embrace more progress than they could have without the self-flattery. (For this reason the walking-on-hot-coals part of the motivational conference is at the end, after all the content that's meant to pump you up.) But lots of firms take this too far and you really see it when they talk about their basically-bog-standard Agile process as if they are Prometheus and have stolen the fire of this sacred process for the benefit of all mankind.

It's possible to significantly improve on this status quo. Here's what that looks like: https://playbook.hanno.co. Please study this.

Hanno's playbook is the output of deep client experience. Some of you will have the chutzpah to create something similar, but without the depth of client experience. I'd bet money that most of those who do never get asked for a case study.

I realize it will feel strange to do this robust a writeup of a process that you haven't been able to apply a lot, but I mention this anyway as an option because you might have a transferable process from your previous work that you could document in a robust and useful way but referring to your new focus instead of the old as you write it up. Some folks can pull this off.

3: Write "The Book" On The Subject #

The final way to bypass needing case studies is to write "The Book" on the subject. Here's what you're aiming for:

- 10 to 20k words

- Professional layout that looks like a normal business book

- Self-published

- PDF/EPUB/MOBI-only, but with the accouterments of a trad-published book (front matter, ISBN, etc.)

If other "The Books" exist, differentiate yours somehow. Don't distribute your book using Amazon KDP or similar unless you want to spend months getting reviews (absence of reviews will be an antisignal), but definitely don't phone in the font matter and layout. Or the content. Don't phone that in either. :)

This focus on front matter and layout is leveraging the way people respond to the signals of authority while also giving them complete access to verify your legit-ness themselves (which case studies really don't) by inspecting your thinking.

For cheap-but-good layout you can use Vellum or similar, or drop a hunned or three on Upwork to get a freelancer to make it look pro.

Your book doesn't have to be results or process-oriented -- it can be a "big idea book" -- it just needs for a few people who are not you to consider it worth reading. :)

If you've never tried it, you might be surprised by how quickly you can get a semi-coherent 15,000 words written and edited down into a coherent 10k (this article is almost 2,900 words), but if for some reason this feels impossible to you (try anyway, please!) then your fallback plan is 3 to 5 1,500-word blog posts that address your new area of focus.

I hope you're surprised by how casually I treat the idea of writing a definitive book on a topic. I treat this endeavor casually because it's easier than you think to actually write this kind of book. I have done it, and I'd put the list of other ways in which I am mediocre human being up against yours any day of the week.

Be Very Up-Front About Having No Case Studies #

Explain not having case studies. I suggest: "This is a new focus for me, so case studies are pending. I invite you to instead check out X." and then promote whatever of the above you've done.

Likewise, don't neglect the low-hanging fruit of credibility:

- A good /about page on your site

- A LinkedIn profile

- A good-but-not-cheesy headshot/portrait

- A sufficiently-serious social media footprint. Don't be a robot or a business broetry artist, but do use your social media presence to show that you put serious effort into your expertise and also have a life outside of that; an 80/20 to 50/50 split on the expertise/life content is about right.

My assumption in all of the above is that you'll be willing to do the hard thinking now and get paid for it later. This is a reversal of the usual workflow with freelancing where you get paid 50%, do some fairly-specific-to-that-project thinking and doing, and then get the other 50%. Some of us are happy to take a different deal all day long: do some more-broadly-useful thinking now, get paid nothing up front, and then price and sell that thinking over and over again for 20 or 30 years. This is what entrepreneurship without venture capital or a big team of employees looks like, and the math on it can be quite good.

Go Deeper:

Invest In Questions #

Get as good at asking probing/why questions as possible. You could do a lot worse than committing to the "Five Why's" approach and trying to get as many opportunities to practice that as possible.

Explore Other Risk-Reduction Options #

I've never had the balance of low-effort "keep the lights on money", savings, and ambitious level-up opportunities needed to offer a money-back guarantee on work, but that is one way to reduce risk for clients. Here are some other useful ideas: https://jonathanstark.com/types-of-guarantees

Why I Don't Recommend Free/Reduced-Cost Projects In Exchange For Case Studies #

You could try to do a small project or three for reduced rate/free in exchange for proof from the client. I don't like this idea as much as any of the above, but I do generally think it's OK to do strategically-valuable stuff where you trade current cash for future opportunity of some sort, but you probably have bills to pay so you have to apply this approach surgically and sparingly.

Additionally, some projects really depend on your client being emotionally invested in the project and actively working to prioritize it. I call this client buy-in. Client buy-in often tracks with the price on your invoice, and reduced price leading to reduced buy-in can translate to reduced results. That's the worst possible outcome: you take a haircut on revenue and unintentionally encourage your client to de-prioritize the project, causing unimpressive results and unimpressive proof for you.

Often enough, there are plenty of prospects out there who will pay full price even without the case studies and give you the proof you need after the project, so why give up the money and risk getting lukewarm results?

This all depends on lots of variables, and if the thing you're wanting to get proof for doesn't require a ton of client buy-in (ex: give me access to your AWS infrastructure and I'll audit for obvious security holes), then trading a discount for the proof you seek can work fine. But think carefully about this before you go down this path to getting case studies.

Summary #

If what you do is commoditized (RFPs are sometimes issued), the lack of case studies may be a problem, but I don't think it'll be an across-the-board dealbreaker. I realize my proposed workarounds are laborious, and until you try it yourself this core uncertainty will remain: is your thinking as expressed through a vivid diagnosis, a robust process description, or a "The Book" compelling enough to get clients excited or trusting enough to bypass a request to see case studies?

I worry that if you try this and find that your thinking is currently not good enough… I worry that you'll be discouraged from further developing your thinking so that it is compelling enough. But I've learned that I worry about a lot of stuff I shouldn't. My hope is that you stress-testing your thinking in this way is exactly what you need to leap into a new level of expertise, authority, and a more profitable service delivery model.

Good luck!

I hope that this article has been useful. If you’re looking for more context and detail on specialization and positioning, then read my free guide to specialization for indie consultants.