A Complete Guide To Specializing And Positioning An Independent Consulting Business

LLM-Generated Summary

A summary of A Complete Guide To Specializing And Positioning An Independent Consulting Business, generated by Claude-2 (and not edited by me for accurancy or anything else), using this prompt:

Please write a complete and detailed summary of the text below. Please do not omit from your summary any seemingly important ideas, arguments, or details. Please do not try to make your summary short; aim for 'lossless compression' rather than 'lossy compression'. After your summary, please list both the strongest and weakest arguments in the text, and list potential counter-arguments against the strongest of the author's arguments.

Here is a detailed summary of the key points made in the text:

The text provides a guide for independent consultants to specialize their business in order to avoid the common pitfalls of ineffective marketing and services becoming commoditized.

It first explains why most marketing fails - people tend to misunderstand, ignore or distrust it. Services also naturally become commoditized over time as information spreads, supply increases, and prices fall.

Specialization is presented as the solution. By narrowing your focus, you make your services clearer, more memorable, and easier to build expertise and trust in. This helps counter the human tendencies causing marketing failures. Specialization also differentiates you from competitors, keeping you out of commoditized markets.

There are 5 main ways to specialize:

- Vertical - Focus on a specific industry vertical or closely related ones.

- Audience - Focus on a group of businesses with a commonality, across industries.

- Horizontal - Focus on solving a specific business problem or achieving a transformation.

- Platform - Focus on a specific software platform.

- Service - Specialize a specific service offering rather than the whole business.

The text then provides a 6 step process for deciding how to specialize:

- Assess current situation - Inventory past experience, interests, access to markets.

- Assess risk profile - Gauge your tolerance for uncertainty, loss, volatility.

- Create a shortlist - Use your inventory to identify attractive, lower risk opportunities.

- Apply guardrails - Validate market size, competitors, accessibility.

- Choose validation approach - Options are pivot blindly, guardrails only, research, market test.

- Implement - Declare your focus, build a marketing platform, cultivate an ecosystem over time.

In conclusion, specialization takes time, courage and discipline. But it enables consultants to build expertise, trust and avoid commoditization. Iteration is normal, go deep over time.

Strongest argument:

- Specialization makes your services more memorable, understandable and trustworthy to a niche target audience. This directly counters the human tendencies that cause most marketing to fail.

Weakest argument:

- Platform specialization has easy entry but high hidden risks of the platform changing or commoditizing the ecosystem. However, the risks are not fully explored.

Potential counterarguments:

- Specializing may reduce overall lead flow, at least initially, by narrowing your appeal. This risk could have been addressed more fully.

- For solo consultants, horizontal specialization across industries may be more practical than vertical specialization. The text focuses more on vertical.

- Doing extensive validation before specializing may be impractical. A phased approach starting with guardrails may be more pragmatic.

The Guide

This guide will help you specialize your independent consulting business. But first, we have to deal with some bad news.

The default condition of marketing is failure. Most marketing simply fails to work.

Likewise with services, the default is for services to become commoditized; to become bought and sold like identical, easily-replaceable, low-priced commodities. Even consulting services.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that specialization helps you override these defaults and market your services in a way that works while avoiding the gravitational pull of commoditization. This article will guide you there.

Why Marketing Fails

The default response of a human being to seeing your website or other artifacts of your marketing is to misunderstand or ignore it.

The default response of a human being to hearing what you do for a living is to quickly forget it. (How quickly have you forgotten just the name of a person you’ve just met?)

The default response of a prospective client to hearing about what you can do for them is to not trust you.

These are defaults that are wired into human behavior, and it’s these defaults that cause most marketing to fail.

Al Ries, in his book on positioning, describes the problem of information overload from the perspective of someone living in the early 1980’s, before we invited the Internet and ubiquitous wireless computing into every corner of our lives.

The level of information overload Ries was describing circa early 1980’s has been amplified many times over since then. It’s primarily this modern information hyper-overload combined with our ancient human hard-wiring that causes the default human behavior, and it’s this default human behavior that causes most marketing to fail.

Most independent consultants don’t do the work required to override these human defaults; the work of clearly defining our services in a memorable way that also earns trust. This work often brings up paralyzing amounts of fear, so we tend to avoid it. And as a result, our marketing fails to earn sufficient visibility and trust for our services.

Why Services Commoditize

You’ve heard the saying, “Information wants to be free” — a simplification of something Stewart Brand said once. Whether it’s universally true or not, this saying holds true when it comes to the commoditization of services. It explains part of why services become commodities: the information needed to build the skill needed to deliver many services wants to be free, and it wants to spread. As it spreads, the supply of skill increases, and the rarity and therefore the price of that skill goes down.

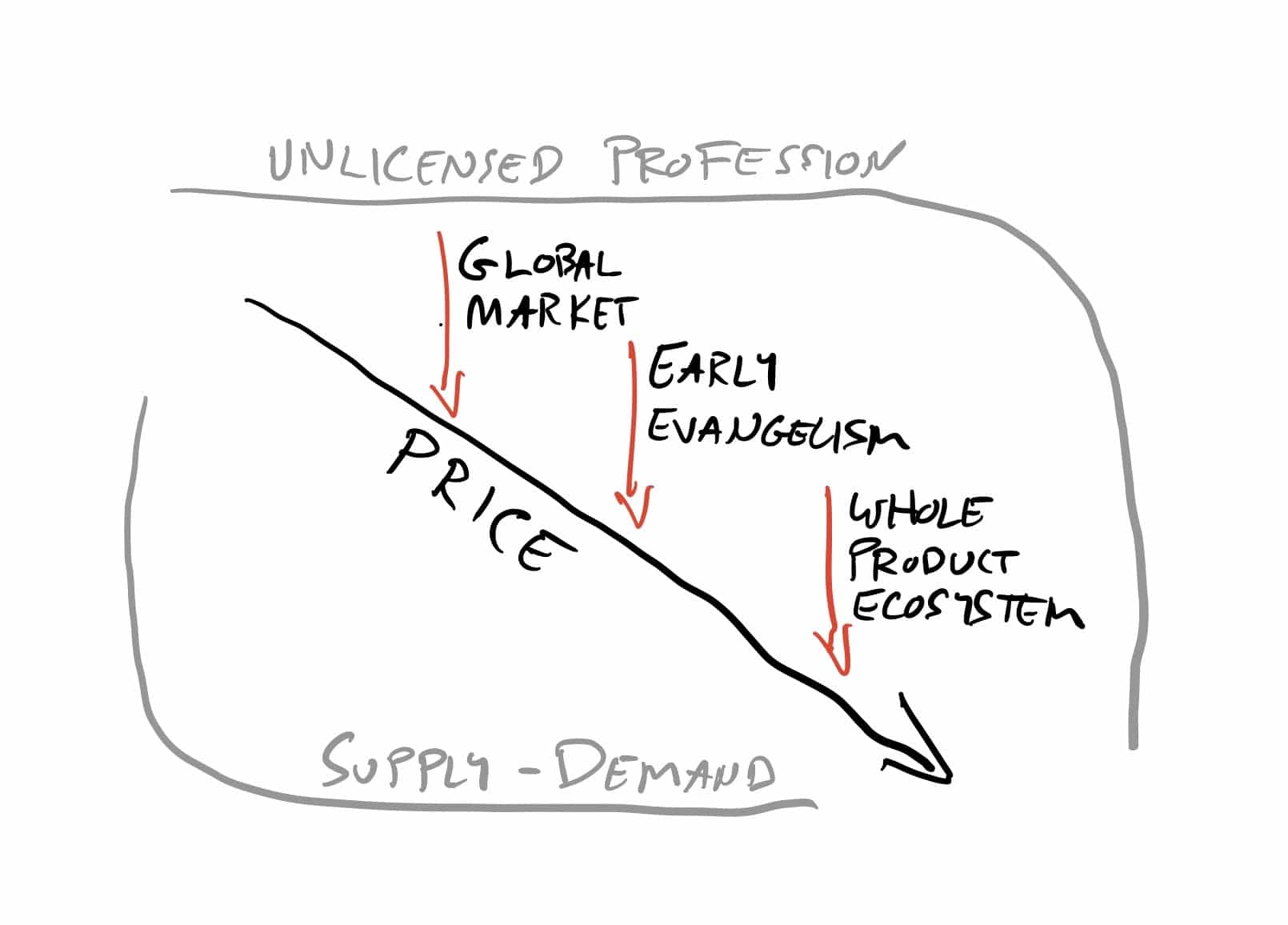

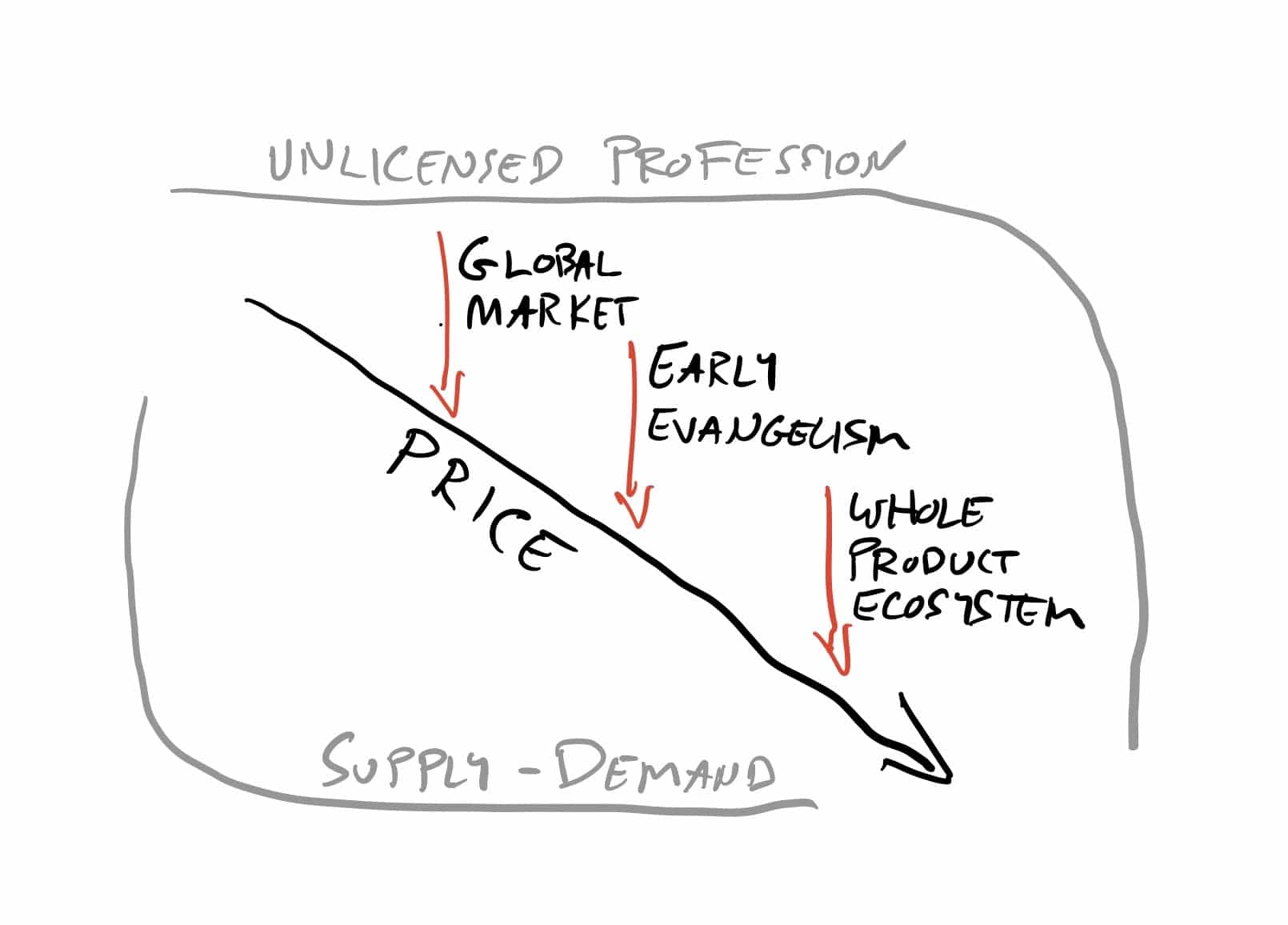

That’s part of why services commoditize over time. Here’s the full system-level view:

1: Unlicensed Profession

Most independent consultants are unlicensed professionals. This is both our superpower and our kryptonite. It enables us to capitalize on small, emerging opportunities with flexibility and speed using self-made expertise. And on the flip side of this golden coin is a large global supply of competition, unrestrained by licensing or advanced educational degree requirements, happy to undercut us on price. There’s no professional standards body limiting the supply of licenses or working to coordinate among all of us to ensure we all make a good living.

The fact that most of us practice a fully unlicensed profession creates the context which facilitates commoditization.

2: Global Market

It’s not true of every service offered by every independent consultant, but many of us can work with clients fully remotely. That means that anyone who shares a common language and sufficient timezone overlap with our clients can compete with us.

This creates a global market, and a global market covers a large difference in cost of living for its suppliers. Some of your and my competition can live on far less than we can. I pay $120/mo for a 150 megabit symmetrical fiber internet connection; a Russian I spoke to recently pays the equivalent of $5/mo for a faster connection. I have some advantages he cannot replicate, and he has some advantages — many of them cost-related — that I cannot replicate. If he was a competitor, he could offer something similar for less money, and some buyers will find that attractive.

3: Early Evangelism

The nimbleness enabled by our practice of an unlicensed profession means that many indie consultants are focused on new or emergent areas of practice. In these areas, there is little or no established best practice; almost no corpus of how-to information.

So, we produce it ourselves. We become evangelists for our area of practice by publishing how-to information. This functions as very effective content marketing. There’s little search engine competition, and so it’s an easy win to turn our early expertise with an emergent practice area into opportunity-generating content marketing or indie educational products like online courses or books.

As we do this, we are paving a highway onramp for our competition and accelerating their learning. In the early days of our emergent opportunity, the more practitioners the merrier. As this process continues, however, those competitors we helped create eat more and more of the bottom and middle of the market.

4: Whole Product Ecosystem

If your area of practice is focused on a platform (a few examples: AWS, Entrepreneurial Operating System, 3 Highly Achievable Goals, React), then the platform vendor or custodian wants to drive adoption. One way they can do this is reduce the risk for the early majority, late majority, and laggard adopters. They do this by working to build what Geoffrey Moore calls a whole product, which is a complete ecosystem of product, reliable vendors, and implementation support (certification, training, good documentation, best practices, supporting frameworks to ease implementation, etc). Platforms that have bought into Moore’s whole product idea are highly motivated to build out and facilitate this ecosystem because without it they believe they won’t achieve mainstream adoption.

Every element of a whole product ecosystem facilitates services commoditization. The platform wants to make you, a “vendor”, interchangeable with any other vendor in order to lower risk for those who haven’t adopted the product. Sure, they need a few incredibly talented experts, but they need a lot more competent, commoditized vendors.

5: Supply-Demand

Finally, the market forces of supply and demand are always there, working tirelessly to equalize prices.

Consider the software developer in Ukraine who invests all of their free time for 6 months learning React. They’re able to dramatically increase their rate while still undercutting developers who live in any US and most European cities.

Or consider the small-time small business management consultant in Birmingham, Alabama who devours the Entrepreneurial Operating System books, gets certified, and starts to become part of your prospects’ choice set.

Or imagine the aspiring brand consultant in anywhere-cheaper-than-where-you-live who just read Storybrand and decided this is the future of their career.

These people — we were just like them at one point — are entering the supply side of the market and offering an increasing array of choice to the demand side of the market, but because they are entering an unlicensed profession (1) from all quarters of a global market (2) in which early evangelists (3) and platforms (4) have created a robust corpus of how-to knowledge and best practices, their offerings are largely un-differentiated. That is to say, standardized and interchangeable. Commoditized.

As indie consultants, commoditization should scare us a bit. As members of the human race, it should excite us. Commoditization makes the chaotic and risky into the standardized, ordered, and predictable. Commoditization paves the way for higher forms of order. On the whole, commoditization is a big win for the human race. Specialization is a way to make sure you don’t lose as part of that deal.

NOTE: It is somewhat ironic that in publishing this article and my book on positioning, I am doing something to commoditize a service I offer. I’d be delighted if I accomplish this. Perpetrator of commoditization is different than victim of commoditization. In fact, self-commoditization can be a critical part of the indie consultant’s path to greater impact, profitability, or scale.

Specialization Is The Antidote to Marketing Failures And Commoditization

Specialization is the act of narrowly focusing your business. This is both an important strategy decision, and an effective antidote to the problems of marketing failures and commoditization.

There are 5 ways you can focus your business; I’ll cover those shortly.

The default response of a human being to seeing your website or other artifacts of your marketing is to misunderstand or ignore it.

If you narrow your focus sufficiently, you make your services easier to describe and easier to understand. In a recent consultation with a 60-person agency, “Reimagine Digital” became “Drupal for the Enterprise”, a considerable increase in the clarity of the firm’s self-description.

The default response of a human being to hearing what you do for a living is to quickly forget it.

If you narrow your focus sufficiently, you make your services extremely relevant to a small group of prospects, and for those prospects your services become more memorable. Not for all prospects or the entire market. You don’t need that. You need a high level of relevance to a small group of prospects, and specialization accomplishes that.

The default response of a prospective client to hearing about what you can do for them is to not trust you.

When you specialize, you become an insider. You won’t become a highly connected, highly trusted insider quickly. That takes time and work. But you will become an insider rather than an outsider, and in so doing you’ve become a member of a new social group. Humans tend to trust members of their social group more than outsiders.

Western cultures confer elevated social status on experts. Experts are almost always specialized.

Much of how we humans make determinations about the status of others is based on a rapid, often subconscious process of feeding sensory perceptions into mental heuristics to arrive at a determination of status. To choose just one example, the signal might be: being seen driving a luxury car, and the heuristic is one that associates driving luxury cars with high status. (Is the driver a valet taking the Bentley for a joy ride? The mental heuristic doesn’t care.) In another example, the signal might be: wearing a white lab coat with stethoscope around the neck, and the heuristic is one that associates these objects with expert status.

These status heuristics get us close enough to the truth often enough. They save our cognitively-stingy brains lots of energy and do so with little risk of harm, so we use these imperfect heuristics almost every time. We develop these heuristics individually through observation, and we receive them ready-formed as a cultural inheritance.

Part of this cultural inheritance is a heuristic that confers relatively high status on specialist experts. Even if we didn’t receive this heuristic from the culture, we would arrive at it through observation that:

- Specialists often go through specialized, advanced, or simply grueling training.

- Specialists can fix certain problems faster, better, or more easily than generalists can because of their depth of specialized experience.

- Specialists are able to ask for and receive more financial compensation for their labor or thinking or expertise than those without any specialized expertise.

- Generalists seem to outnumber specialists, so there must be something unique or different about specialists, and those with the courage to be different (the relatively rare specialists) must have a good reason for doing so.

- Specialists tend to value their own specialization or expertise and protect it through licensing or standards, and this self-valuing passes for confidence much of the time, and confidence sends signals that we associate with high status.

Is it true that specialists are more important, and therefore worthy of higher social status, than non-specialists? It doesn’t matter, because there are enough heuristics out there running on autopilot inside the minds of enough people that we — at least in Western cultures — act as if specialists are of higher status.

The elevated social status of specialists makes it easier for them to quickly earn trust.

Competitors entering an unlicensed profession (1) from all quarters of a global market (2) in which early evangelists (3) and platforms (4) have created a robust corpus of how-to knowledge and best practices create undifferentiated offerings. That is to say, standardized and interchangeable. Commoditized.

If you narrow your focus sufficiently, you make your services meaningfully different from your competitors because your competitors tend to be competent generalists rather than focused experts. [2] Your narrow focus exposes you to more repetitions of similar problems in a shorter timeframe than your generalist competitors will have access to. This gives you an expertise-building advantage, which helps you move up the value chain from implementation-only services to advisory-only or advisory+implementation services. Commoditization consumes the bottom and middle of markets, usually leaving the high end (advisory, architecture, strategy, and so on) intact while creating new opportunities elsewhere.

Narrowing your business focus by specializing is an antidote to marketing failures and commoditization because it makes your services clearly understandable, memorable to the right prospects, and able to earn trust more readily. This focusing also gives you an expertise-building advantage that helps you move out of the bottom and middle of the market, which are the parts that get consumed by commoditization.

Terminology: Specialization vs. Positioning

The words positioning and specialization compete to describe the same idea. When I have my positioning consultant hat on, I work to distinguish them.

- Specialization is the decision you make about how to focus your business.

- Positioning is a word that describes the process of seeking and earning a specific, desired location in a market, otherwise known as a market position.

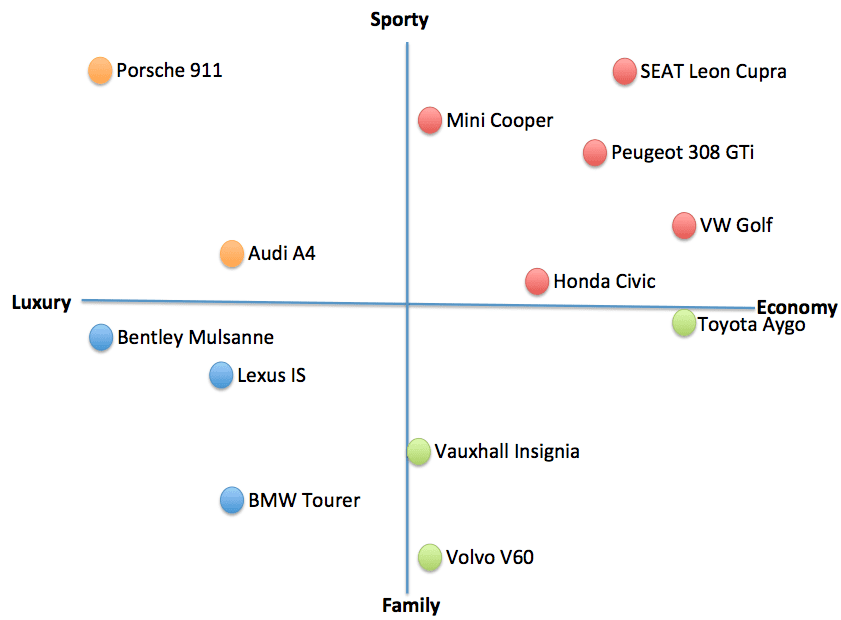

Here’s an example (source: smartinsights.com) of one way to visualize the market position of several cars:

I favor using the word specializing instead of positioning because when we make the decision to specialize, we control more of that process. We can seek or aspire to a market position, but we can’t make it happen quickly, nor can we guarantee that it will happen. In the world of services, we build up a market position incrementally over time.

By their very nature, services are delivered mostly in secrecy, witnessed by only a very small group of people at a time. The reputation that we earn by delivering our services grows slowly, usually one client at a time. Products, especially ones with a significant revenue stream or real funding behind them, can reach many more people many times more quickly than our services can. A product’s reputation can grow much more quickly. Yes, there are exceptions to this. For example, the right article published in the right publication could certainly accelerate reputation-building for the right services business, but expecting slow-ish organic growth of your reputation will cause you to be right a lot more than you’re wrong.

For that reason, it’s sensible to talk about positioning a product. The product, via its marketing amplified with advertising spend, can be relatively quickly moved into a specific desired location in a market. It can be positioned like a chess piece.

If the product must change to fit a desired position in the market, it can change. People (the source of services) are usually less malleable. Moving a person into a specific market position, especially one requiring significant expertise, can’t usually happen as quickly. With us humans, change is usually incremental and laborious. Incidentally, this is why a separate category of advice about specialization/positioning needs to exist for services firms. The advice about positioning products contains assumptions that don’t apply to us.

The decision to specialize, combined with disciplined followup over time, leads to a market position, which we can think of as a reputation. Not everyone in the world or the target market needs to know of your reputation. If enough potential clients in a market are aware of your reputation as a specialist, you have earned a market position.

How many potential clients is enough? That depends on a lot of factors, and can never be exactly quantified except by observing the desired outcomes of sufficient opportunity and increasing profitability. Rest assured, though, that you can start with a very small number of potential clients being aware of your reputation as a specialist and things will work out fine. 6 potential clients is the record for what I’ve seen: /consulting-pipeline-podcast/matt-krause-starting-with-a-niche-of-6-clients/

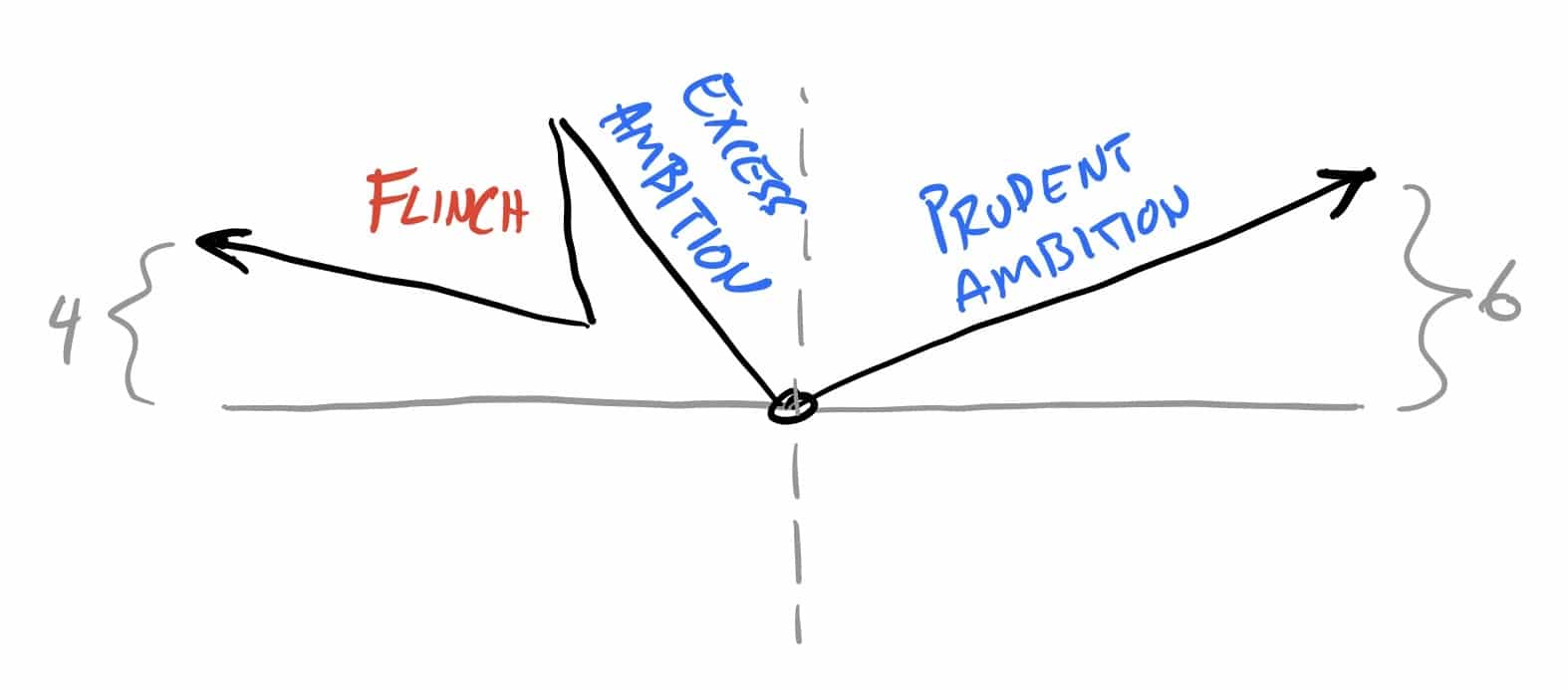

Enough Time To Flinch

Again, earning a good market position requires deciding to specialize, then following up that decision with an implementation period. The implementation requires 3 months to 3 years of work. That work looks like reputation building through focused client work and focused marketing.

Some independent consultants decide to specialize and get an instant ROI on the emotional discomfort of doing so. Maybe they mention the new specialization to a colleague or someone in their network and immediately get connected with an opportunity that would have previously been out of reach for them. Or maybe the specialization decision unlocks a flood of energy and ideas about marketing that quickly translates into new opportunity.

It’s more common, though, for the implementation period to involve some emotionally tough spots. Some longer-than-we’d-like moments when the market doesn’t seem to care, or the specialization doesn’t seem to be working. Or alternately, perhaps the specialized opportunity we’re seeking finds us and then intimidates us. Imposter syndrome kicks in, causing us to doubt whether our expertise is sufficient. 3 months to 3 years is long enough for us to experience at least one of these tough spots.

During these moments, we can “flinch”. Flinching is overreacting to the normal features of the landscape we journey through while implementing a new specialization. We interpret a lengthy stretch between prospects that fit our specialized focus as a sign that the specialization decision was bad and consider returning to a generalist focus. Flinching means losing courage and discipline and becoming fear-driven and un-disciplined, which generally undermines our claim of focus.

You can recover from a flinch like this and resume your progress towards that specialized market position you want to earn, but the flinch slows you down. I’d prefer to see you make steady progress uninterrupted by flinches, even if it means choosing a less ambitious form of specialization.

Flinches are caused by exceeding your risk profile. Risk profile is an idea borrowed from the world of financial planning, where the idea of risk tolerance is approached with more nuance. What most of us think of as risk tolerance is actually 3 components:

- Your emotional comfort with uncertainty

- Your physical ability to sustain loss or harm

- Your composure in the face of volatility

Your unique blend of these 3 components defines your risk profile. It’s useful to think about your relationship to risk in this way because, for example, you might be very emotionally comfortable with uncertainty but also unable to sustain much financial loss, and so you should actually make more conservative decisions than you might think if you only looked at your high level of emotional comfort with uncertainty.

There are 5 things that make a specialization decision risky:

- Insufficient access to prospects

- Insufficient credibility among prospects

- Insufficient insight into the market

- Insufficient demand for your specialized offering

- Insufficient interest — on your part — in your area of specialization and your clients needs

A following section of this article walks you through how to make a good specialization decision. This process incorporates these 5 elements of risk to help you avoid exceeding your risk profile.

There’s one more important piece of groundwork before we get to that decision making process.

There Are 5 Ways To Specialize An Independent Consulting Business

Let’s understand the 5 ways you can specialize.

Seeing them all listed out before we explore them in detail helps folks build an understanding of these 5 specialization approaches. Here they are:

The Vertical Specializations

- Pure vertical specialization: focus on a market vertical.

- Audience specialization: focus on a group of business that have something important in common but are in different verticals.

The Horizontal Specializations

- Pure horizontal specialization: focus on a business problem.

- Platform specialization: focus on a platform.

The “Oddball” Specialization

- Service specialization: specializing a service rather than the entire business.

Remember that specialization is an antidote to commoditization because specialization allows you to more quickly cultivate valuable expertise. You can’t do that if your specialization isn’t tightly focused enough. That’s why most expert specialists will be focused on one, maybe two complementary market verticals at once. Or one, maybe two related business problems or platforms. Bear that in mind as you read about these 5 market positions.

Specialization 1: Pure Vertical Specialization

One of the most common ways the world of commerce is divided up is based on what kind of stuff a company sells. If a company sells property and casualty insurance, it gets grouped together with all the other companies that sell that kind of insurance, and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) assigns the code 524126 to this group of businesses. Direct Property and Casualty Insurance Carriers is a market vertical. There are 1,039 other market verticals identified in the NAICS system.

Some market verticals are too small to support your business, most are too large to represent a sufficiently narrow focus. Learn more about some well-researched guidelines for market sizing here

Pure vertical specialization happens when you decide to focus on a single market vertical, or at most 2 closely-related verticals (ex: medical and life science). You do your thing, whatever that is, exclusively for a specific market vertical. Some examples:

- Distance learning program design for higher education

- I help biotech startups use storytelling to articulate their strategy to investors

- Marketing for manufacturing

You’ll notice a range from broad vertical focus (manufacturing, higher education) to specific (biotech startups). That’s fine and normal, and the narrowness of your focus will be driven by factors specific to your business and your goals. You’ll also notice a range from broad “what-you-do-for-your-clients” (marking) to specific (distance learning program design, strategic storytelling). That’s also normal and fine, though a soloist may not be able to deliver an entire broad discipline like marketing; that might require a team.

Specialization 2: Audience Specialization

An audience is a group of businesses that share something important, even if they’re distributed across multiple or all verticals. Non-profits, mission-driven organizations, venture-funded startups, women-owned businesses, and independent consultants are examples of audiences. This is by no means an exhaustive list! Like market verticals, audiences are numerous and widely varying in size and culture.

Audience specialization is similar to pure vertical specialization because audiences often have clearly identified “watering holes”; places where they congregate and interact with each other and with specialists that have focused on them.

Vertical Specialization Pros and Cons

No way of specializing is universally best. They all have pros and cons. When you specialize vertically (pure vertical or audience), it becomes easier to proactively find and reach out to your prospects, but you do run the slight risk of a vertical-specific downturn (ex: COVID and higher education) or legislation reducing your supply of opportunity.

Specialization 3: Pure Horizontal Specialization

It’s easiest to understand pure horizontal specialization by starting with a few representative examples before we define the idea:

- I help businesses save money by improving their inventory management.

- I help businesses increase performance by using storytelling to align employees around company strategy.

- Bilingual and bicultural marketing

- I help businesses design incentive programs that motivate call center workers.

- I help businesses use open source software to gain strategic advantage.

You’ll notice that the focus is on solving a problem (wasting money through substandard inventory management), optimizing something (motivating call center workers, aligning employees around strategy), or some more radical transformation (expanding into a new market where language or cultural barriers might be a barrier, using open source software to gain advantage).

We can define a pure horizontal specialization as a focus on a business problem, optimization, or transformation. Your focus isn’t constrained to a single market vertical; you’ll work with any business in any vertical if they need your horizontally-specialized expertise.

Specialization 4: Platform Specialization

Platforms can include:

- A business process framework (ex: EOS, 3HAG, Six Sigma, Agile, Lean, TDD)

- A programming language (ex: Python, Ruby, C#)

- A framework (ex: React, VueJS, Laravel)

- An actual platform you can build stuff on (AWS, Linux, Windows, Salesforce)

A platform is a “thing” — often but not always a product — that lots of businesses use and need help understanding, planning for, implementing, operating, extending, supporting, fixing, optimizing, and upgrading.

You can specialize in a platform. Often this is the easiest way for technical folks to specialize. Be warned that the low price of entry to a platform specialization is subsidized by some hidden risks that you need to understand.

The Hidden Risks of Platform Specialization

The most apparent risk of platform specialization is that you don’t control the platform. Let’s say you have earned a market reputation as someone who is great at helping large, complex sales teams implement Salesforce. You wake up tomorrow to the news that Salesforce has launched a professional services division, and their marketing for it points out that their professionals have direct access to product engineers (something you don’t have) and therefore can resolve issues faster than anyone else and, oh also, if you buy a 3-year service contract, the implementation phase is free. That’s a made-up but not-farfetched and rather vivid example of how your lack of control over the platform is a significant risk.

The less visible risk of platform specialization is how the platform ecosystem is rather “bipolar” over time. Platform ecosystems generally start out as fluid, open environments that reward consultants who can “figure shit out”, even if it’s expensive. They evolve towards rigid, commoditized environments that reward businesses that can consistently deliver quality at scale with low or moderate cost. Those are two very different kinds of businesses, and so as a platform ecosystem evolves, you’ll either have to evolve your business into one more suited to a commoditized environment or jump ship to a younger platform, which is risky and expensive for you. In technology, many platforms reach maturity in about 7 years, which is not a lot of time for this kind of business evolution. I expand on this more here: /indie-experts-list/the-death-of-a-market-position/

Horizontal Specialization Pros and Cons

It’s easier to imagine how a horizontal specialization (pure horizontal or platform) will remain interesting and challenging over the long haul. While it’s not actually true that a horizontal specialization is automatically more interesting than a vertical one, to the specialization newbie it usually seems so. This may lower the emotional barriers to entry for you, allowing you to successfully specialize horizontally and then possibly add a vertical focus at a later time to further narrow your specialization. If you’re a solo indie consultant, specializing horizontally may be more compatible with your small business size than vertical specialization, which can often require a team of people to deliver a complete solution.

When you choose a pure horizontal specialization, you usually face a more difficult business development task because proactively finding and reaching out to prospects may be impossible, and the sales cycle is often longer or more unpredictable.

When you choose a platform specialization, you choose to compete within an environment that will eventually commoditize, and so you are choosing to take on the future risk of whether you can successfully navigate the platform’s eventual commoditization.

Specialization 5: Service Specialization

Finally, service specializing is narrowly focusing a single service offering rather than specializing your entire business. The service offering can be focused horizontally or vertically, just like the entire business could be.

For some, service specialization is a way to test the waters of specialization in a way that feels less risky. For others, it’s a way to land on a “beachhead” from which you plan to pivot the whole business in a different direction. And for others — usually freelancers who are approaching their business somewhat casually — it’s a way to increase profitability by bringing some productization or repeatability to their service delivery.

I hope the brevity of my description here doesn’t come across as disparaging service specialization. For some risk profiles, it’s going to represent a big win, and I celebrate that. For some emotional temperaments, it’s the right kind of incremental move away from being stuck as a generalist, and I celebrate that too.

A Process For Deciding How To Specialize

None of the 5 ways of specializing is naturally superior; they all come with tradeoffs in terms of risk and business development difficulty. But one of them will be right for you and your business, and there is a repeatable process for arriving at that point of clarity. Here’s an overview, followed by DIY-level detail on each step:

- Assess your current situation by inventorying past experience, areas of interest, and entrepreneurial theses.

- Assess your risk profile.

- Create a shortlist of specialization opportunities.

- Apply guardrails to your shortlist.

- Choose depth of validation for your shortlist options.

- Implementation.

In guiding hundreds of business owners through this process of specializing, I’ve observed 3 patterns that describe how they make the decision. We tend to do one of the following:

- Leverage a head start.

- Pursue an interest in serving a particular kind of business or solving a particular kind of problem.

- Pursue an entrepreneurial thesis.

I’ll briefly explain each.

Leverage a Head Start

A head start is some relative advantage that you possess. Building on an advantage is a specialization accelerant and a risk reducer, at least compared to undertaking the same specialization journey without that head start.

You can specialize without any particular head start, but if you ignore a signifiant head start, you’re making more work for yourself. You might decide to do this for good reasons, but understand what you’re giving up by ignoring that head start.

Head starts generally take the form of one or more of these advantages:

- A significant depth or quality of access, or large number of connections, to a target market.

- A significant amount of credibility in a market vertical or within a certain audience.

- A significant depth of expertise in some area.

- A significant depth of insight into a target market’s needs or business realities.

- A significant ability to earn trust from prospects or clients.

Find Your People/Opportunity

What kind of clients do you prefer to serve, or what problems do you find most fascinating and compelling? Folks who use the Find Your People/Opportunity approach to specializing choose their focus based on an aspiration to work with a certain type of client or problem rather than a head start that gives them a relative advantage there.

Note: “Clients that pay their invoices on time” is not a valid choice here. You need to define a target market horizontally or vertically, not based on personal preferences that make you look weirdly picky or self-centered.

The Find Your People/Opportunity approach to deciding how to specialize is more risky. This is a good place to remind you that for all the power, reach, and flexibility that modern digital marketing gives us for generating leads, and for all the power that Google and LinkedIn give buyers for finding solutions they may not have been aware of before they searched, you’re still in a relationship business.

Your ability to forge trusting relationships with buyers is the beating heart of your ability to run a thriving consulting business. This doesn’t mean you need to be an extrovert or have world-class people skills. Lots of nerdy introverts, like myself, do it without those qualities. The risk the Find Your People/Opportunity approach poses to you is that you could choose to specialize in a way where it’s difficult or impractical for you to forge trusting relationships with enough buyers to make it work.

If you’re using the Leverage Your Head Start approach, you’re probably going to specialize in a vertical or problem you have past experience with. You’ll know what to expect. You may already have a useful amount of access to buyers or credibility. With the Find Your People/Opportunity approach, you may be moving into unfamiliar territory with surprises in store for you. The solution, of course, is to do some market research to make the new territory less unfamiliar.

Entrepreneurial Thesis

The final decision making approach I’ve seen out in the wild is what I call the Entrepreneurial Thesis. This is actually a variation of the Find Your People/Opportunity approach, but it’s better suited to someone who is more mercenary or entrepreneurial in their overall orientation to risk & opportunity. This mercenary or entrepreneurial orientation is often correlated with a reduced need for craftsman-like enjoyment of the work. Or perhaps the craftsmanship shows up in the design of the business rather than the delivery of services.

Instead of looking for what kind of clients you prefer to serve, or what problems you find most fascinating and compelling, you are looking for the opportunity that seems like the best bridge from your current position to a significant entrepreneurial opportunity; one that you can scale with process, people, or intellectual property.

These three decision making approaches are baked into the process below, so you don’t have to explicitly choose one of them to use. I’ve listen them in order of riskiness. Leveraging a Head Start is the least risky way to specialize, while the Entrepreneurial Thesis is the most risky. I wanted to explain these approaches at this point in this article because they provide helpful context before we dive into the actual decision making process. That’s next.

1: Assess Your Current Situation

The decision making process I’m about to describe begins with a written inventory of your previous experience. I know you have all this information in your head, but writing it down does a few important things. First, it helps you remember everything; writing things down just seems to do that as a natural by-product. Second, it helps you remember more objectively, with less emotion and less of the “fog of war client work” interfering. And finally, it helps you spot patterns more readily when it’s all written down.

You should definitely create your inventory using a tabular tool like a spreadsheet. It will make organizing it and looking for patterns much easier.

Inventory the following items:

Vertical Inventory: Inventory everything you’ve ever done for clients, employers, and any substantial side-projects. For each thing in your inventory, include:

- Client name

- Market vertical that client is in

- The business outcome of what you did for that client

Horizontal Inventory: Add to your inventory all horizontal abilities you currently have that help you move the needle for clients. The following are examples of horizontal abilities:

- Increase conversion rate on e-commerce stores

- Reduce downtime for critical infrastructure

- Integrate ERP with other systems

- Reduce cognitive load of using software

Entrepreneurial Theses Inventory: Add to your inventory all entrepreneurial theses you’re interested in possibly pursuing.

The difference between this and the horizontal inventory is that you might have to put together a team, or rent skill you don’t have, or build something that requires up-front investment, or just generally take on more risk — perhaps by pursuing a specialization you just can’t validate but you believe deeply in — as part of building your market position.

Next, extend your inventory: Add to it all verticals that interest you, even if you haven’t worked in them before. Make sure you have an uninterrupted hour or two before you do this next step.

Go to https://www.naics.com/naics-drilldown-table/. Slowly read every top level item in the list of market verticals there.

Pause after you read each item. Let your imagination wander a bit. Ask yourself the following questions:

- “Is there more to this market vertical than I might think at first?”

- “Are there possibly companies in this market vertical that are struggling to effectively use technology that I have experience with?”

- “Would companies in this market vertical possibly get excited about the potential of what I could build for them?”

- “Does this market vertical have smart consultants like me throwing themselves at it, or is it likely to be under-supplied with tech talent?”

As you do this, you are looking inside yourself to see if there is movement towards or away from each market vertical on the NAICS list. When you consider a market vertical like, let’s say pharmaceuticals, does your imagination light up at least a little bit? Or does it contract at the thought of dealing with companies in that vertical? It does not matter why, you are simply looking for a subtle “yes” or “no” from your inner self.

If a market vertical gives you that subtle yes, then click into that top-level vertical on the NAICS site to explore the subcategories. Do the same kind of inquiry for each subcategory.

Add any NAICS subcategories that interest you — ones that you get a subtle yes to — to your inventory. It does not matter if you have never worked in the vertical before. Just add it to your list.

Also add all horizontal abilities that interest you, even if you have only a poorly developed version of these abilities. The NAICS list won’t help you with the ideation here, so try to think about problems or ways of improving a business that are a) interesting to you personally and b) likely to effect businesses across multiple verticals.

Quantifying: Go back through your inventory and score each item according to the criteria below. As you do this scoring, use a scale of 1 to 3 (whole numbers only) to keep things simple and avoid analysis paralysis. 3 represents a lot of something (access, credibility, etc.), and 1 represents very little of it.

You’re using a spreadsheet for this inventory, right? If you’ve listed each item in your inventory on a different row, then just add columns to keep track of the score you give each item along each of these aspects:

Access: how deep does your business or personal network extend into this market vertical or area of opportunity? Score from 1 (very little) to 3 (a lot).

Credibility: how credible will prospects find you? Have you produced results for them before? Can you “read their mind” during a sales conversation? Score from 1 to 3 (whole numbers only!).

Impact: For rows on your inventory that describe actual client work (rather than verticals or horizontals or entrepreneurial theses that you are interested in but have never worked in before) score the impact your work had for your client. Did it make them money, save them money, increase efficiency, or help them achieve a strategic advantage of any kind? If so, that’s impact. Your scores should be relative to other work your business has done, not work other businesses or your competitors have done. Score from 1 to 3. (For example: imagine you have completed a project in each of 3 different verticals. The projects saved your clients 5%, 7%, and 10% of something, respectively. At one of those clients, you are aware a competitor saved that client 15%. You would rate the impact your work had at each of those 3 clients based on your performance, not your competitors performance.)

Profitability: For rows on your inventory that describe actual client work, score how profitable the work was for your business. Score from 1 to 3

Interest: What is your personal level of interest in this area? If you’re a small firm or soloist, your ability to delegate away uninteresting stuff may be limited, so set a low score for stuff you’re un-interested in. Score from 1 to 3

2: Assess Your Risk Profile

There’s no “scientific” way to measure risk or a person’s risk profile. This is part of what makes it such a fascinating phenomenon to study. It’s somewhere between falling in love (quite mysterious; very unmeasurable) and predicting the weather (possible but always imperfect).

If you find this upsetting, that in itself tells you something important about your relationship to risk: you dislike the uncertainty part!

That said, your answers to a few simple questions about your feelings about and behavior with uncertainty, potential financial loss, and volatility can lead you to a reasonable understanding of your risk profile. As you answer these questions, you certainly can try to fool yourself, but that’s on you. :)

If you attempt to give honest, objective answers, this risk profile self-assessment will be more useful.

Here it is: /risk-profile-self-assessment/

Please take a few minutes to complete this self-assessment now.

3: Create A Shortlist Of Specialization Opportunities

At this point, you almost surely have a big, messy inventory. Let’s turn it into a more usable shortlist.

You’re using a spreadsheet for this inventory, right? I hope so, because I’d recommend at this point you add two columns containing formulas:

Aggregate score = Impact score + Profit score + Interest scoreRisk score = 7 - Access score - Credibility score

At this point, each opportunity described in your inventory has a rough quantitative score describing the potential attractiveness of that opportunity and the risk of that opportunity. Is this scoring perfect? No. Can you totally delegate your decision making to this score? No.

What you do have is a simple, useful way to prioritize opportunity and weigh risk. This is profoundly useful for moving you into a more objective place from which to make the specialization decision.

Sort your inventory in a way that puts opportunities with the highest Aggregate score at the top of the list.

Flag opportunities that are too risky. You’ve got your risk profile score from the self-assessment, so flag any items on your inventory that have a risk score that’s higher than your risk profile score. The measurement scale of the risk profile self-assessment is designed to match the measurement scale of the inventory risk score, so you can use your risk profile self-assessment score as a simple “risk threshold” and discard items on your inventory that exceed that risk threshold.

Now flag opportunities that have one of the following deal-breaker flaws:

Low importance: Buyers see the service offering as un-important. Trying to change their perception is somewhere between difficult and impossible, so treat this as a deal-breaker flaw.

Excessively long buying cycle: If you have the runway to handle a long buying cycle, great! But if you don’t, it’s a deal-breaker flaw.

Accessibility: A market with 10,000 prospects that you can’t reach is the same thing to your business as a market with 0 prospects. Do you have a repeatable way to access at least a few buyers or decision-makers or recommenders? If not, then you’ll need to create one to successfully move past this potential deal-breaker.

External forces: Are any external threats to your market apparent? Keep in mind that external forces (changes in regulation, disruptive competitors, economic impacts focused on a single sector) are not always a threat to you even if they are a threat to your clients. Your value as a specialist consultant may come from helping your clients navigate external threats.

Marketing approach: Do you understand what marketing approach will work well for the prospects you want to reach? You can not dictate to your prospects which marketing approach is ideal for reaching them. They get to decide that, and you can only decide whether you want to work with their preferred approach(s) or be ignored.

You now have an inventory that’s sorted by the attractiveness of the opportunities, and you’ve flagged specialization opportunities that are potentially too risky or suffer deal-breaker flaws. You have a shortlist.

4: Apply Guardrails To Your Shortlist

Next, you are going to apply “guardrails” to the specialization options on your shortlist. This part of the process is full of judgement calls and a need for your creativity and problem-solving ability.

For every vertical specialization option on your shortlist, use LinkedIn Sales Navigator to find accounts (that’s LinkedIn’s term for companies. You’re not looking for people at this stage of things, you’re looking for companies). You’re looking for accounts that match the vertical you’re investigating.

For example, perhaps you have the Manufacturing vertical listed on your inventory. Annoyingly, LinkedIn does not have that vertical listed in the Industries search field. LinkedIn does, however, have many of the sub-verticals within Manufacturing listed in its Industries search field. This is where your creativity and problem-solving ability is required to construct a decent search. This list of LinkedIn’s industry categories may be helpful: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/linkedin/shared/references/reference-tables/industry-codes

Use a column on your inventory sheet to document the number of prospects (companies that are probably big enough to afford you and small enough to take you seriously) in each vertical on your shortlist.

It has always been difficult to validate a horizontal specialization, because the market demand that drives these kinds of specializations is somewhere between difficult to measure and outright invisible. The best reasonably easy proxy measurements are forms of documentable interest. If there’s existing competition, that’s evidence of interest in this area of specialization. And if there are existing ecosystems of support (conferences, forums, online watering holes, etc.), that’s another form of evidence that you might be able to make a horizontal specialization work.

Use a column in your inventory sheet to document any evidence of interest you can find.

To discover competition, you’ll want to use a combination of web search (Google, etc.), directories (Clutch.co, etc.), and LinkedIn Sales Navigator.

To discover ecosystems of support, you’ll want to use web search and any other tricks you can make use of (asking in an online group you’re already part of, etc.).

This is challenging work! That’s why we’ve saved it until towards the end of the process: to make sure you deploy this high-effort work only on shortlist items that are interesting to you.

Here are the guardrail criteria I’d suggest you use:

- If a potential vertical specialization has fewer than 1,000 prospects or more than 10,000 prospects, re-define the vertical or remove it from your shortlist of options. Re-defining the vertical might mean finding a sub-vertical with fewer than 10k prospects or finding a broader version of a tiny vertical that has fewer than 1k prospects. These numbers are based on David C. Baker’s well-researched numbers with his lower bound of 2k tweaked downward to reflect the fact that many of you are soloists: David's numbers

- If a potential specialization of any kind has fewer than 10 competitors or more than 100 competitors, it’s a risky option because the presence of too little competition (< 10 competitors) is a proxy for too little market demand and the presence of too much competition (> 100 competitors) signals a “red ocean” full of excessive competition. If you’re pursuing an entrepreneurial thesis, it’s normal for there to be little or no competition, but if you want a low-risk specialization, eliminate or re-define shortlist options that have the wrong amount of competition in the market.

- If a horizontal specialization has no ecosystems of support, remove it from your shortlist of options. Yes, you can make a horizontal specialization work even if there are no ecosystems of support, but it’s harder, so this guardrailing criteria suggests that you remove these more difficult options from your shortlist.

After you do this step, you will end up with a “shorterlist” of specialization options. Specialization hypotheses, if you will.

5: Choose Depth Of Validation

The most beautiful specialization hypothesis in the world is worthless if the market doesn’t care within a timeframe that matches yours. That’s why we seek validation for our ideas — our hypotheses — about how we might specialize our business.

There are 4 ways you can validate:

- Blind pivot

- Guardrail-and-go

- Deep market research

- Live market test

Blind Pivot: A blind pivot is only considered validation based on a technicality. With a blind pivot, you choose the specialization hypothesis that seems best to you and go with it. You assess, create a shorterlist, choose the one that seems best to you, and implement. You “just do it”. Validation or invalidation of your hypothesis eventually happens, but it takes months or years, and risks business failure and opportunity cost.

A blind pivot is post-validation rather than pre-validation.

Guardrail-and-go: You choose from your head start or your heart and apply sensible guardrails (healthy market size, documented interest, etc.) to eliminate excessively risky options. After that, you choose the specialization option you like the most and implement. You can also simply copy a specialized competitor and implement. With the Guardrail-and-go approach, you are not validating directly with the market, you are looking at proxies for market demand (presence of competitors, etc.) and using the presence of those proxies as evidence of sufficient market demand.

The guardrail-and-go approach is quick-and-dirty pre-validation. You’ll notice I’ve already told you to apply some guardrails in the previous step of this decision making process. That’s because the ROI on this work is high enough that it’s worth doing no matter what. I don’t consider it an optional validation step; it’s just a natural part of the right way to make a specialization decision.

Deep market research: With this approach, you reach validation through market research interviews with buyers in the market you might focus on. Your research might actually generate the hypothesis, as is done in innovation-focused research, or it might validate/invalidate your specialization hypothesis. Research styles include Customer Development (Cindy Alvarez) & JTBD (Alan Klement).

The deep market research approach is time-intensive pre-validation. I rarely recommend this approach anymore except in cases where you’re pursuing an entrepreneurial thesis.

Live market test: With a live market test, you build a free gift of knowledge for the market, directly distribute it (1:1 emails or LinkedIn messages, posts on intimate forums or Slack/Discord channels), and ask for feedback on the gift. There are other ways you could run a live market test (run ads pointing to a landing page, etc.) but for indie consultants, directly distributing a free gift of knowledge and pointedly asking for feedback on it is the best approach.

For most indie consultants, the live market test is a good middle ground between the deep market research method, which has considerable time cost, and the guardrail-and-go method, which generates no actual evidence from the demand side of the market.

Again, the most beautiful specialization hypothesis in the world is worthless if the market doesn’t care within a timeframe that matches yours. The live market test delivers visceral evidence about whether the market cares about your potential way of specializing.

But! How much validation you invest in is up to you. It’s your decision. Some of you will have the risk profile and existing business momentum to do less validation. Others will want to extensively de-risk the decision by carrying out more validation. If you decide to de-risk by doing some validation before you implement your new specialization, I recommend the live market test.

6: Implementation

At some point you have to move out of analysis and validation mode and into implementation. At some point you have to take action on your specialization decision. This is often the point at which more fear surfaces, so let’s go through a “FAQ lighting round” to address the irrational parts of this fear before we talk about implementation:

Q: Do I have to fire clients outside my new focus?

A: No! Start pursuing new specialized opportunity, but don’t harm your business by firing clients you can’t afford to fire. Unless you can afford to do it more suddenly, go for a gradual transition. Try to replace generalist clients with specialized ones one client at a time.

Q: Will my current generalist clients drop me if I specialize?

A: I’d bet against this happening and I’d win most of the time. Most of your current clients aren’t exposed to your efforts to develop new business, and if you don’t proactively tell them about your new focus, most of them will never know. That said, you probably should tell them about your new focus (they might have leads for you!) and reassure them that it doesn’t reduce your level of commitment or service to them.

Q: Will putting the new specialized focus on my website or LinkedIn profile reduce my lead flow?

A: Maybe, but if you’re like most indie consultants, your website generates almost no lead flow anyway; leads tend to come from elsewhere. If there is a reduction in your lead flow, it’ll either be temporary, or it won’t be a reduction, it’ll be a shift in the kind of leads from a mostly-unqualified to mostly-qualified leads, or a change from generalist leads to specialized leads. In other words, the reduction will happen in parallel with an increase in lead quality.

Implementing a new specialization requires the following:

- A declaration of focus

- A marketing platform for visibility, connection, and trust

- A few other things are helpful, like an ecosystem of support, time, and courage

A Declaration of Focus

You need your new focus to be very clear to prospective clients. How you declare this focus to them depends very much on how specifically you earn visibility and trust.

For most of us, our website is the logical place to begin our declaration of focus. It seems like a high-stakes change, but it’s usually not because for most unspecialized indie consultants, the website generates a minority of your lead flow.

There are also other venues where you can declare your new focus:

- Email marketing content.

- Social media presence(s), like your LinkedIn profile, etc.

- Sales conversations with prospective clients, where you verbally declare your focus in the privacy of that conversation.

- Off-site content marketing (things like talks, podcasting guesting, etc. that happen places other than your website)

- Your personal and professional network.

Keep your declaration of focus simple. Like, “cave man speak” simple. Prospects will appreciate the lower cognitive load, and will feel like you don’t have anything you’re trying to hide behind excessively complex language.

Don’t try to perfectly qualify clients on your site by having a long checklist of stuff you’re looking for. That overly complicates things for prospects, runs the risk of alienating good prospects by making you seem strangely picky, and adds friction. If you’re at a place in your career where you’re drowning in good leads, of course ignore this advice and add the right kind of friction to make sure you only spend valuable phone time with good prospects. But those earlier in their career can gain an outsized benefit from one simple thing: more conversations. Keeping the message on your site simple can help avoid confusing prospects. This increases the number of conversations you get the opportunity to participate in, so keep things simple!

Be clear and avoid waffling. If in doubt, use one of the following recipes for your site headline:

- [Thing you do] for [Market you do it for]

- Ex: Custom inventory management solutions for manufacturing

- [Service] for [target market]

- Ex: Customer satisfaction surveys for cosmetic dentists

- [Result] for [target market]

- Ex: Reduced inventory management cost for multi-location retailers

- I/We help [primary audience/market vertical][description of solution/result you help them achieve]

- Ex: I help Fortune 500 CEOs ghost write best-selling memoirs

- I/We help [primary audience/market vertical][description of problem you solve for them]

- Ex: I help custom software development shops fix their lead flow problem.

- I/We help [primary audience/market vertical][description of problem] without [contrast against limitations of competing solutions].

- Ex: I help dev shops grow their revenue without adding junior developers.

- I/we help [primary audience][description of solution] with [brief summary of how the solution works]

- Ex: I help real estate agents become top producers using unique video marketing solutions.

- If you [description of problem], then [promise of result or CTA to learn more about you]

- Ex: If you would like to attract more talent without paying expensive and unethical recruiters, talk to me.

A Platform For Visibility, Connection, & Trust

There’s more than one way to model how a stranger becomes a client for expertise-driven services, but the following is a reasonable one:

- You become visible to them.

- You establish some kind of connection with them so the relationship continues.

- You earn their trust and so they come to believe that you could fix, optimize, or transform some part of their business. You may become an authority to them.

- When they’re ready, they seek to elevate the relationship from audience membership to client.

There’s a lot going on in that model. You’ll notice that it’s all framed in terms of really human things like trust, relationships, status, and so on. For indie consultants, I believe there’s no other way to view it.

That hasn’t stopped the marketing profession from draining the warmth and blood from these very human things and coming up with cold, transactional terms like lead generation, lead nurture, and conversion to describe the same process I’ve described above. It’s OK to use these terms, but I try not to because I find they subtly pull my mindset in the wrong direction, away from relationships that create business value and towards transactions that de-humanize.

Additionally, a strange thing happens when you try to distinguish between lead generation and lead nurture activities: you find that the most effective of those activities can both generate new leads and nurture existing leads. They are both lead generation and lead nurture activities rolled into one. Said in more human terms, you find that the most effective marketing activities for indie consultants can both help new people become aware of your expertise & services (visibility) and earn more trust from those who are already aware of you.

A client of mine helps businesses use open source software and open source thinking to create strategic advantage. He’s very effective at giving talks at conferences. At some conferences, some attendees have never heard of him. His talk helps them become aware of his expertise. At those same conferences, there are people who are already aware of his expertise. For some of those people, the same talk at the same conference earns sufficient additional trust that they begin a sales conversation with him.

The simple term for all the stuff that creates visibility and connection, helps you earn trust and authority from those who have connected with you, and leads to opportunity is… a marketing platform. This is different than the kind of platform we explored earlier.

If you can regularly share your thinking in an impactful way with an audience, you have a marketing platform. Marketing platforms include but are not limited to:

- An email list of people who have opted in to hear from you regularly.

- A relatively engaged social media following.

- Access to publications that help you reach the audience you want to reach. You don’t have direct access to those publications subscribers (your access is mediated by the publications), but you have access to the right gatekeepers, and so you have a sort of “virtual platform” made up of your access to the right group of gatekeepers.

Building a marketing platform is an important part of implementing a specialization decision. Most of us default to thinking of our website as our primary marketing platform, but for most of us our website is the least effective marketing platform we could build.

Things get more clear if we ask: “what is a marketing platform for?” What’s its purpose?

A market platform creates visibility for your expertise and services, and it helps you connect with and earn trust from an audience that is interested in those things. The ultimate purpose of a marketing platform is to build authority in the market. We can think of authority as trust in someone’s expertise. It’s a particular kind of relationship, and in this relationship specialization + authority + a relevant offer -> consulting opportunity.

The right approach to building a marketing platform is to spend 80% of your effort on the following foundational work and use simple, low-tech tools to share your thinking with your audience.

The foundational work:

- Choose a narrow focus so you know exactly who you’re trying to connect with and earn trust from.

- Gain insight into their world, so you know exactly what value you are creating for them.

- Cultivate a point of view so that your marketing is meaningfully different from others with a similar skillset or body of experience and so prospective clients are able to see something attractive or repellant in you.

- Build a body of work that demonstrates real, deep expertise rather than commoditized skill. This body of work might focus on solving your audience’s problems or it might focus on helping them achieve an aspiration, but either way it will be valuable to them. It must, in fact, be valuable to them.

Simple, low-tech tools for earning visibility, connection, and trust from an audience include:

- Anything that leverages an existing authoritative publication (trade publications, someone else’s podcast or event, etc.) for getting your thinking in front of your target market.

- Email list. Don’t allow yourself to use fancy segmentation, lead scoring, personalization, or complex digital marketing funnels until you get a comment from at least 10 strangers on the strength of your expertise or POV. Generally avoid using urgency, fear of missing out (FOMO), or fear-baiting anywhere at all.

- Anything that relies on RSS for distributing content. A blog, hosting a podcast or guesting on others’ podcast.

- Curated, small group realtime interaction with your audience. It’s OK if the tech that facilitates this is somewhat complex as long as the experience for participants is intimate and high quality. It’s fine if you’re listening to them, learning from them, speaking to them from stage, teaching them, or demonstrating expertise to them. All of those are trust-building forms of interaction. Selling aggressively to them as a group is not.

- Still worth including on this list but less desirable: Making use of a social media platform to share your thinking.

Building a marketing platform takes time and experimentation. There’s no single recipe you can follow that will work for every independent consultant. Building it takes real work.

After you’ve decided how you will specialize, you’ll find that some of the difficult or confusing parts of building a marketing platform have become easier to figure out. You’ll have much more clarity about who you need to reach, and you’ll have better ideas about how to reach them. This new clarity makes beginning the work of building a marketing platform easier.

Other Helpful Assets:

Let’s conclude the implementation phase with a few more assets that will help you build a good market position.

- Ecosystem of support

- Time

- Patience, discipline, and courage

Eventually, you’ll need an ecosystem of support. Remember that what we’re talking about here is the list of things you need to turn your specialization decision into a strong market position. Remember that your market position is your reputation. Remember also that you’re in a relationship business.

One of the ways you can cultivate the reputation you want is to recruit the help of other people:

- People who can refer you when the right kind of prospective client asks them for a referral.

- People who can get you in front of their audience and help you connect with the right kind of prospective clients.

- People who can call attention to your work because it’s relevant to their audience.

- People who have a complementary product or service who can refer you to their customers or clients.

- People who admire your work and spread the word without you asking them.

One of my coaching clients is cultivating a relationship with a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reporter whose beat (the intersection of tech, business, and culture) overlaps with my client’s focus. My client is playing the long game of slow, gradual engagement, starting with social media interaction. Eventually, this WSJ reporter will be part of my client’s ecosystem of support. I don’t know exactly how or when, but I call this out here because it’s a good example of what I mean by an ecosystem of support. You can run your business alone, but you can’t reach the highest possible level of success without other people.

Cultivating an ecosystem of support is something you can do intentionally, but it’s not something you can develop a granular, precise plan for. It’s much more about keeping an ear to the ground for beneficial relationships and opportunity, and then taking action when they present themselves.

The final group of assets you’ll need to implement a specialization decision are time, patience, discipline, and courage. They go together because they are the human stuff — the grit and heart — that you bring to the process. They are vital ingredients in the asset you are trying to build.

Parting Words

I’ve helped hundreds of people, many of them indie consultants, specialize. In this article, I’ve tried to give you the most concise version of what I’ve learned along the way (there’s a more expanded version of this available in my book The Positioning Manual for Indie Consultants) if you want to go super deep. I’ll leave you with a few more tips

You’ll iterate. That’s normal. Don’t thrash, though. Remember it takes time because you’re building a reputation, and you don’t want “reputation thrashing”.

You can enjoy the marketing results of specialization and call it a day, or you can go crazy-deep into specialized expertise, which is a multi-year or multi-decade endeavor. The choice is yours. I hope you go the deep expertise route, but I salute your victory no matter which way you go.

If you’re on the fence about specialization at this point:

- Focus on your curiosity rather than your indecision. Give yourself permission to experiment without making any externally-visible changes to your business. You can experiment “off the books” with stuff like email outreach and specialized services.

- Follow the process of steps 1 – 5. Let the experience of the market validation help you understand whether specialization feels right for you. If you want support doing this, consider coaching.

Remember: the market wants to ignore you. You have to work to change that. You can. Many others have done it. But it takes work and consistency (and a positive attitude helps).

I wish you the best luck with this life-changing work!

Notes:

1: I should point out that you can run a good business in a commoditized market, but see this article for more on why you may not be well-suited to do that: /indie-experts-list/the-death-of-a-market-position/

2: A recent study of the Drupal market found 70% of firms describing their focus in generalist terms. Not quite the Pareto 80/20 split, but not far away from that distribution.

More resources to help with the journey from generalist to specialist

Kindle/ePub/PDF Versions Of This Article

(No opt-in required)

More How-To Articles On Specialization

TODO: include "_tpmficbookcta.html"

TODO: include "_listscta.html"

https://github.com/mondeja/mkdocs-include-markdown-plugin