Gifted designers can stretch established forms in delightful ways, but for 98% of us, if we publish a book it should look like a normal book, and if we publish a website for our specialized business, it should look like a specialized business website. Let's explore what that looks like.

In this article I'll avoid showing specific examples to help you avoid over indexing on any one specific design or approach, but you can browse a range of worthy examples at http://specializationexamples.com

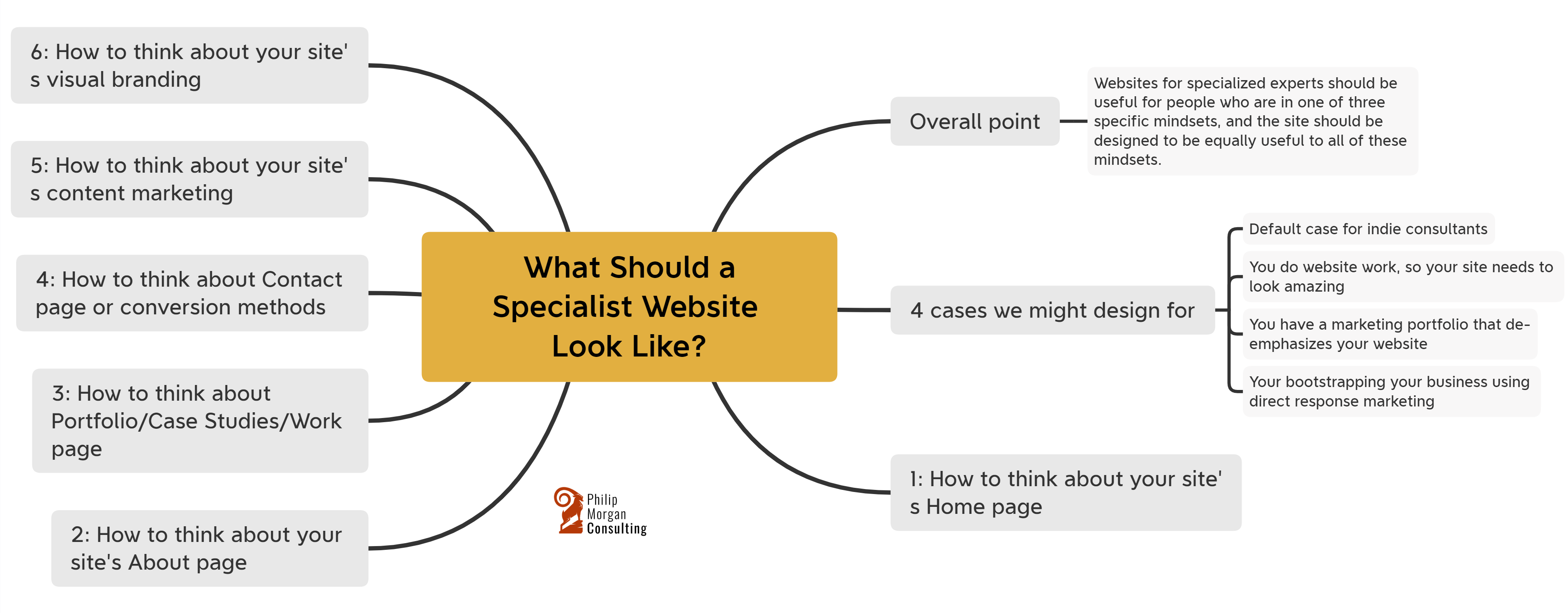

TL;DR #

This article is longer than most of my question-focused articles. I'll start by giving you the ability to hit the eject button before you finish the article and still leave with something useful: websites for specialized experts should be useful for people who are in one of three specific mindsets, and the site should be designed to be equally useful to all of these mindsets. This equality of usefulness does not mean that website content or functionality is equally distributed between all 3 mindsets.

-

Idle Curiosity - A client of mine was describing his competitors and mentioned Andy Raskin. I had never heard of Andy Raskin, so I searched his name and visited his website. I skimmed the home page and left with my idle curiosity satisfied. I know roughly where Andy Raskin fits within the world of indie consultants. I am no longer ignorant of who this guy is and what he does and am less likely to look uninformed, which would be a risk to my social status. This is the idle curiosity mindset.

-

Single Question/Problem-Solving Campaign - When I started working for myself, I was terrible at it. I went in search of answers to the questions I had. I found helpful answers on Brennan Dunn's website, and read many of the articles there. I was engaged in a (pain-driven) campaign of problem-solving involving deep, effortful research, and I evaluated sites I found through the lens of whether they helped me progress towards my purpose of being better at self-employment.

-

Active Buyer - Is it obvious how to buy what you sell? What are the steps? What are the knowns and unknowns in the buying process? What kind of budget does the buyer need to show up with? This is the information that someone in the active buying mindset needs to easily find on your site.

If you stop reading now, take this with you: a good specialist website serves the purpose of all 3 of these mindsets. If you can find ways to effectively serve those 3 mindsets, you'll create a good specialist website even if you don't have a model to adapt or the specific guidelines I lay out below.

To add a quick metaphor that I'm borrowing from Expertise Incubator member Jim Thornton: a good specialist website is like an Ikea. It has both a useful showroom and a useful warehouse.

I was living in Portland, OR when the Ikea store opened there. Ikea's brand power made me curious about what it would be like to shop there. As soon as I could, I visited the new store. I don't remember what, if anything, I bought, but I remember needing to experience what Ikea could do for me, and that first visit to their Portland store positioned Ikea within my mental map of options for navigating modern life. It satisfied my idle curiosity.

Ikea has a useful showroom where all their answers lie. "Will this sofa fit?" "How could I arrange a small room to maximize the storage?" "What does an efficient kitchen look like?" "Could my bedroom be more comfortable?" These and thousands more questions are answered by wandering through the Ikea showroom, just like many of my beginner level freelancer questions were answered by Brennan Dunn's website. Ikea's showroom teaches you to be a better furniture customer.

When you're ready to buy, you move from the Ikea showroom to the more warehouse-like part of their store. The experience here optimizes for efficiency. You know what you want or need, and this part of the store gets the products in your hands, collects payment, and gets you out the door as efficiently as possible. This matches your mindset of transactional purpose quite well.

A good specialist website functions like an Ikea.

Know Which of the Four Cases You Are Designing For #

There are four business situations, or cases, you might design your website for. When I say "design", I am talking mostly about the approach to content and information architecture, though visual design matters too. These 4 cases are about your needs rather than your website visitor needs.

The default case for indie consultants: The marketing approach is light on direct response marketing and heavy on usefulness and brand marketing gifts. We've studied examples of those who don't need the money but ferociously seek impact and hybridized what we learn from them with our constraints and need for short-term revenue.

Special case #1: You do website or website-tangential work for clients, so your site needs to "demonstrate the product" and needs better design/visual branding than the default case. This is 100% fine, just bear in mind that you will need a more visually beautiful or impressive version of what I am describing in this article.

Special case #2: You've built a "virtual platform" across multiple platforms like Medium, Twitter, YouTube, live talks, etc. Your website has secondary importance compared to your presence on these other platforms and your site might function more like an online business card.

Go Deeper on the Virtual Platform Concept: The Un-Owned Marketing Pltform

Special case #3: You're bootstrapping using direct response marketing (DR) and you want to leverage the DR approach as much as possible because it works and it works efficiently. In this case, your website will be more like a collection of landing pages that are tied together by your email list (and/or email automation), and you will not invest as much in a robust, useful information architecture for your on-site content.

Go Deeper on DR vs. Brand Marketing: Brand Marketing and Direct Response Marketing for Indie Consultants

These special cases are all legitimate reasons to depart from the default case described below.

How to Think About Your Site's Home Page #

In the default case, here is how you should approach your site's home page.

Present a clear, simple, blunt positioning statement in large font at the top of the page.

Add a subheading if you must. The subheading has this job: add clarity, nuance, or additional differentiation to your headline. Avoid watering down the focus of your headline, adding empty filler words, or being too clever or jokey.

In the past I've said said your home page has 1 job: to get email signups. I now recant (unless you fit into special case #3). The job of the rest of your home page — everything below the headline — is to:

- Summarize what you can do for clients.

- Implicitly ask visitors if they're "just browsing" or looking for something specific and give them a few corresponding options. This certainly can include an email list opt-in, but getting email opt-ins is not the primary overriding job of the home page. Your choices about home page structure are signaling to both human site visitors and search engine robots what is important, so choose wisely.

- Establish a bit of credibility through basic signals like a physical/mailing address and attractive visual design elements.

You should have a clear, simple menu for navigating to at least the top-level parts of the site (articles, services, about, etc). This is generally located above the headline, but sometimes elsewhere on the page.

How to Think About Your Site's About Page #

Your site will have something like an About page. I think about this like a book's author bio — longer than 2 paragraphs but much shorter than the New Yorker magazine profile of you would be.

This may be a place to play up your insider or outsider status. It's probably fine to include stuff that you think will establish a personal/human connection (dog photos, etc.) with site visitors, but don't feel like you have to.

The About page is often a writing quagmire for us. We get self-conscious; we can be awkward as a result. If you feel this happening, try to think about your About page as an answer to the "why should we hire you?" question and focus on your expertise rather than your personality or your CV.

If you have a robust point of view (POV) or method that guides your work, you could include this in your About page as well. This page can be "About me" or "About my approach to helping you". I used to lean super hard to the latter, but I have to remind myself that we're in a relationship business as well as an expertise business, and so giving some information that would help with the former is advisable.

How to Think About Your Site's Portfolio/Case Studies/Work Page #

Unless it's your metaphorical first day on the job, you will have prior work to talk about or show. Here's how to think about that.

If your abstracted thinking is sufficiently impressive, focus on that rather than the applied thinking. Otherwise, show the applied thinking and make it your mission to make your abstracted thinking impressive enough to displace the applied thinking save for a few credibility-enhancing logos or testimonials.

To flesh out the above a bit… we're answering the perennial question: "should you show a portfolio or work or case studies?"

I lean towards case studies. This is not because I like reading case studies, but rather I like that if you can write GOOD case studies, it means your business probably contains a real process or real intellectual property or achieves results for your clients that are measurable enough to brag about in case study format.

I'm not a case study dogmatist, though, because I sometimes come across these situations where the work is so outstandingly good that it impresses buyers in the visceral way that a case study never could. The work "packs a punch", and these businesses should show their work rather than case studies.

If your work sells itself and the work is the product of a single person, it's going to be harder to scale the business with the usual methods (process and people) and build up actual IP. And likewise, if you don't have an actual process, skill, or expertise differentiator, your attempt at a case study is going to be too thin.

If you're honest with yourself and this is you, then think of being able to create a good case study -- one that actually demonstrates a unique method or expertise -- as an accomplishment that you work towards by… building a unique method or expertise. That's the real prize you're going for anyway.[1]

If you can write a case study that shows a truly unique approach, thinking, or IP, then it means that your underlying business has at least one of those sources of strength.

Go Deeper:

How to Think About Your Site's Contact or Conversion Methods #

I used to think that every page on your site should have one job and that job was only ever one thing: TO GET AN EMAIL ADDRESS. I've changed my mind completely about the latter, but the "one job per page" notion is a good design principle for web sites if you're not too dogmatic about it.

For example, it's not uncommon for a home page to get the most traffic of any one page on a site, and the variety of intent that's bundled up into that firehose of traffic is quite large, and so your home page should reflect and serve that diversity of intent. If you went with the GET AN EMAIL ADDRESS NO MATTER WHAT approach, your home page would be failing to serve its audience made up of people with those 3 mindsets described above. Your home page can serve a wide variety of visitor intent without becoming an unfocused mess or a "warehouse" of stuff.

In other words, the "one job" of your home page is to help a variety of people with a variety of intent get what they need out of your website. Completely serving this variety of intent will take more than just the home page to get the job done, but the home page can do the first step of the process of serving a variety of visitor intent. The Ikea showroom isn't enough on its own — it's part of a system for helping Ikea customers live in better spaces.

For our default case, contact forms should perform some level of screening or qualifying. Not the "geez, are they going to ask for a DNA sample next?!?!" level that you see forms on enterprise business sites doing, but more than you'd do in special case 3 where your goal is maximizing either email list signups or conversations. The screening can be quantitative ("what service do you want?" or "what is your budget?" etc), but a carefully chosen qualitative method can work well. One of my website forms asks the question: "What's your vision for impact?" The qualitative answers to this question tell me 90% of what I need to know about whether someone is emotionally and intellectually ready for the kind of help I offer.

If you can place forms inline in your site in a way that's reasonably subtle, err on the side of more rather than fewer opportunities for site visitors to upgrade from anonymous visitor to email list subscriber or prospect. Don't over-do it, but don't be afraid of more than 1 form per page.

Categorically avoid popups. Yes, they "work". So does carefully embezzling money from your employer (until it doesn't).

It's totally fine to trade stuff (white papers, email courses, etc.) for email addresses on your site, just make sure what you're offering has zero sketchy vibes. The bar needs to be way higher than this incredibly sketchy offer of "free sage" I saw recently:

(Are they running a hippie kidnapping ring of some kind?)

How to Think About Your Site's Content Marketing #

I used to think that We All Must Publish Content Marketing All The Time. Experience has disabused me of that notion. I've seen indie consultants at the $400K revenue point who publish no content marketing. I've seen consultants flip on a webcam, riff on a topic for 5 minutes, publish it on LinkedIn, and then have conversations with VP-level people at giant companies as a direct result (combined with their brand power and network, of course). I have seen a single email announcing a research project turn into conversations that could easily become sales conversations. I have seen a single blog post about upgrading PHP versions turn into dozens of desirable projects for a prospective client. And — gallingly — I've seen people refer to the latter kind of content as thought leadership. (That took me about a week of anger management work to get over.)

A lot of things can work. At one point in the past, almost any kind of content marketing did work to reliably generate new opportunity for quite a few companies. As a result, content marketing got popular and it got professionalized. And then it got industrialized and now we have an Andrew Chen "Law of Shitty Clickthroughs" situation.

There is one place where almost any honest effort at useful content marketing will work in dramatic fashion: that moment when a new platform is exploding in popularity. A recent example is Notion. It's shit software with a confusing UX, but a ton of people fell in love with it and went seeking help to overcome the underlying issues with using it. They were like a zombie horde seeking brains, and almost anyone who created useful content marketing gave them what they were hungry for and many acquired an audience and niche fame overnight. (Yes I'm being over the top here. Notion is not nearly as bad as I make it out to be, and if you're a Notion fan I'm happy for you. :) ) But most of us have carefully weighed the risks of a platform specialization and avoided it, so this platform-driven moment where the Law of Shitty clickthroughs gets suspended doesn't help us.

Despite these obstacles, you should create content marketing anyway. There will be people who write offensively bad stuff that outranks you because they understand the search game better than you (though Jim Thornton can help with this). The content you write today will offend you 5 years from now because your thinking and POV will grow so much in those 5 years. You should do it anyway because 30% of the benefit of an honest attempt at content marketing is generating current opportunity and 70% of the benefit is in improving how you think and articulate your expertise in a live, unscripted situation. Really, REALLY invest in creating useful content marketing and you'll express ideas with authority and style beyond your few competitors. The only catch: you have to do mediocre content marketing work for 5 years to get to this level.

Your specialist website content should strive for two goals: useful and well-organized. Though he's not a consultant, https://jamesclear.com/articles is my current gold standard for useful + well-organized expert content. If achieving this is beyond where you are right now, there are good alternatives:

- Jim Thornton offers a monthly service that helps you progressively optimize a hot mess of content.

- If what's missing is both structure and useful insight, then you need to publish a lot.

- If you're in a commmoditized space and you're willing to play a multi-year game, then you need to publish 3,000 words/month of empathetic, insightful content.

On that multi-year thing: I assume you are playing the long game. Almost all of my advice is predicated on this assumption. Two notable exceptions I'll carve out:

- When you're getting your first site going or are re-designing a site following a decision about specializing, get it done FAST and embrace an iterative improvement approach. If you have more than a few hundred articles or blog posts, then do invest real effort or money into organizing that content well, but build the rest of the site as fast as possible. Imagine that the project is a human who has slit his wrists and will bleed out if it doesn't finish up FAST. (Fast = a few weeks, if it's a website and not a slit wrist.)

- If your website plays a role in a fast-acting direct response marketing effort because your context insists on this approach, then you're in special case #3 and there are others who have advice that is tuned to this situation (Jonathan Stark, Sean D'Souza, most of the Internet's advice on marketing).

Go Deeper:

How to Think About Your Site's Visual Branding #

In terms of how your site looks and works, there are 3 equally important goals:

- It's useful

- It's easy to use

- It's attractive

Again, a gifted designer can stretch established forms in delightful ways, but just like books have coalesced around a standard form with not much variation, the following notes describe the standard form for indie consulting websites:

- Useful:

- For the blog, a reverse chronological index of articles is the least useful organization form. If possible, graduate from this to some kind of topical index as quickly as possible. If it would create value for your audience, curate the topical index to approach what you see James Clear doing.

- For services, focus on this question: what would help a buyer make an effective decision about fit?

- Before buyers have transactional intent, your site should establish mental schema handles. Is the cost of your services closer to that of a car, house, or laptop computer? Is working with you like working with a health coach, outpatient surgery, inpatient surgery, or an ER visit in an ambulance? What will your services do for your buyers status? What non-monetary investment is required? Is there a waiting list? Who else buys this kind of thing? Think about someone who wants to know what their options are and where you fit into that set of options.

- For buyers who have transactional intent, create an efficient buying path; one that doesn't require arcane knowledge or the friction of exploration and discovery.

- Easy to use:

- Avoid clever terms where well-known standards exist. Ex: blog articles are Blog, Articles, or Insight on your menu, not Musings, not Rants, not Brain Farts, etc.

- The TOC on a book is towards the front of the book, not the back. The primary site navigation on an indie consultant website is at the top, not at the bottom.

- Your website will eventually have several books worth of words in it, so consider using the kind of font that would be used for a business book (Caslon or Baskerville, to name two). A useful reference: https://typographyforlawyers.com/

- Attractive:

- In the same way that cultural notions of beauty have changed over time, notions of what makes for an attractive website will change too. At the time of writing a generous use of whitespace, book-like use of typography, avoidance of stock photography, and a concern for usefulness and attractiveness on screens anywhere from 3" to 30" size seem to create an attractive website.

To all of this I should add: I don't build websites for people. There are others who do, and their advice as combined strategists + practitioners should carry significant weight with you: Newfangled, Alastair McDermott, Jim Thornton. If you've got the mental bandwidth for it, average their perspectives with mine. If you don't, just pick the perspective that seems the most objective and implementable to you and go with it.

Final Thoughts on What a Specialist Website Should Look Like #

Your website needs to serve 3 mindsets: idle curiosity, those on a problem-solving campaign, and those who are ready to buy. Effectively serving that second mindset is what makes creating a good specialist website challenging. If you do this part well, you can earn enough trust and visibility to transform sales conversations into easy "how do we get started" chats and to justify premium rates and fees.

I hope that this article has helped you understand what the website for a specialized indie consultant should look like. If you’re looking for more context and detail on specialization and positioning, then read my free guide to specialization for indie consultants.

Notes:

1: I'll be the first to admit I set the bar really high for case studies. 95% of the time, a case study is basically saying "We're awesome because we built something. Here are some photos and few paragraphs of text to prove it.". :-(

Some lesser percentage of the time, a case study is a high level tour of how something was built. Like pancakes are basically a sponge to hold butter and syrup, these case studies are a medium to show that, yes Virginia, there is a non-chaotic process and provide a context for publishing some testimonials. :-|

It's rare, however, for case studies to demonstrate a truly unique approach, thinking, or IP. :-) If you agree with me about the inferiority of anything other than the last approach, why not set your sights there?